Step aboard and discover what it's like to live on one of the most modern research icebreakers in the world for a few weeks in late October.

Long ago, Norway was a frontrunner in polar exploration. Fridtjof Nansen's polar drift expedition aboard the Fram from 1893 to 1896 and Roald Amundsen's dash to the South Pole in 1911 were two high points.

Then things got quiet for a while. The Arctic was explored by the Russians, the Americans, the Canadians, the Germans, and others… but Norway directed its attention elsewhere.

Norwegian research in the Arctic

Research ship Kronprins Haakon was launched in 2018 to change this. It is a “polar class 3” icebreaker, which means it is suited for year-round operation in second-year ice which may include multi-year ice inclusions.

I joined the GoNorth expedition together with representatives from ten research groups from Norwegian universities and research institutes. We headed for the Nansen Basin and the northern part of the Knipovich Ridge to pursue a wide-ranging and cross-disciplinary scientific program.

Introducing the Kronprins Haakon

The ship is equipped with top-modern laboratories, insanely powerful engines, and comfortable accommodation for about 35 scientists.

Accommodation onboard is basic but comfortable. In addition to the bunk beds, the cabin includes a desk and chair, a small sofa and table, a television, a wardrobe and a toilet and shower.

Scientists on board have pointed out that other research ships they have been on have had much smaller cabins. The top bunk is used as a storage space for my suitcase because I was one of the lucky few who did not have to share.

Experiencing the true polar night

The start of the polar night is like a very long sunset. Followed by an even longer night. And then the next day a slightly shorter sunset (or is it a sunrise? Who knows). This continues until the sun stops makes an appearance altogether.

In Longyearbyen, Svalbard's main town, the transition between seven hours of daylight and no sunrise at all takes just two weeks.

Life onboard

A normal day on the Kronprins Haakon starts at 7.30am – if you want breakfast, that is. Meals are served at specific times and you are expected to be punctual.

This is because the crew manning the kitchen has to work efficiently to get to its other unrelated tasks. Kronprins Haakon has a crew of 15-17, spread between the bridge, the machine room, the outside decks and the living accommodations.

The days are long for the crew, who typically work twelve-hour shifts for five weeks in a row, and then get five weeks off. Scientists also have long days.

This is because ship time is expensive and has to be used as efficiently as possible. Sometimes you have to take water samples or fish for plankton at a specific spot and the ship reaches that spot at 3am.

The fact that day and night kind of melt into each other helps, to a degree. Night shift and day shift are not so different when it's dark all day.

Icebreaking

An icebreaker breaks ice. Not by colliding with it directly, but by sliding over it and crushing it with its enormous weight. This is a noisy process. And a shaky one.

As I am writing these lines, we are making our way south through the ice, at 82° North. I am sitting in the ship's conference room, at a conference table just like the ones you find in office buildings.

The difference is that I have been experiencing a relatively non-stop “earthquake” for the last half hour. The conference room is quite far up, on deck seven, so things are relatively quiet.

On lower decks, the vibrations, shakes, and jerky movements are accompanied by very loud noises.

The noises are a mix of low rumblings, loud thuds and, sometimes, the blood-freezing screech of a large, cold block of ice rubbing against the hull. Surprisingly, sleeping through all that racket is not too much of a problem, most nights. It does trigger some very odd, “disaster movie” dreams though.

The engine room

The ship is like a small power plant. It has four diesel engines capable of generating a whopping 17 megawatts of electricity. Generally, the ship just needs a fraction of that power.

But pushing through ice requires a lot of energy. The ship's fuel tank has a capacity of nearly 1.5 million litres.

To make use of the energy generated as efficiently as possible, the heat from the off gas is used to warm up water. The generators themselves need cooling, which is provided by sea water which cools down fresh water through a heat exchanger.

The hot freshwater is then used to heat the various rooms of the ship, and to prevent ice from accumulating in the ship's moonpool.

The moonpool

The moonpool is a trapdoor in the ship's main hangar that leads directly to the ocean. It opens much more slowly than similar trapdoors in James Bond movies, and there are no piranhas below.

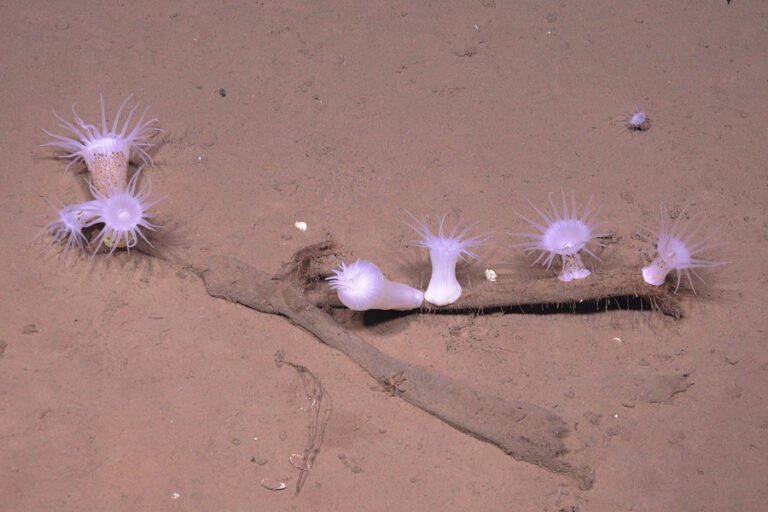

On this trip, the moonpool was used to launch ÆGIR 6000, the expedition's ROV (remotely operated vehicle), capable of reaching depths of 6000 metres.

The food

A nice surprise for a research expedition novice such as myself was how incredibly delicious the food is.

The honour for that goes for the most part to the chef Kenneth Reece, a friendly Swedish guy who became a chef in his forties, training at the Cordon Bleu school in Bangkok. Yes, he is a Swedish chef and has been made aware of how funny that is…

Lamb shanks were served with a red wine sauce and garnished with a gremolata – a mix of fresh parsley, lemon zest, lemon juice, garlic, and olive oil. “I add parmesan to mine”, Kenneth says.

The meat fell off the bone and the combination of flavours was on par with what you would expect at a fine restaurant.

His actual title is Chief Steward. This means that in addition to preparing the food, he is responsible for ordering and managing the ship's stocks of food and other supplies such as toilet paper, hand soap, laundry detergent and such.

The ship sails for weeks on end with no possibility of resupply, and both crew and scientists need to be well-fed the whole time. Kenneth needs to send in his orders a couple of weeks in advance, so careful planning is crucial to make sure not to run out of anything while avoiding overspending.

Once the ship is at sea, his priority is to prepare varied and delicious menus, but also to minimise waste as much as possible. He monitors the state of his produce daily and makes sure to serve his fruits and vegetables before they go bad.

At the time of writing this, we have been at sea for two weeks and we still have fresh fruit and vegetables. I don't know how he does it.

The mission

The ship's mission this time around is to gather information about the area just north of Svalbard, which was designated as Norwegian in 2009, by the UN's Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf.

Topics range from biology to ice research, but the main focus is on geophysics – namely seismic profiles.

This is when a ship uses air cannons to send sound waves to the bottom of the ocean to discover what lies beneath.

This area of the Arctic Ocean has been the subject of few such investigations, due to the difficult conditions caused by the sea ice. You can read more about the science taking place onboard on the project's website: GoNorth.

Très intéressant è lire. Ce n’est pas souvent que l’on connaît une personne qui travaille de près avec des scientifique. Avec les belles photos on se croit presque sur le bâteau avec vous. Bonnes recherches. J’ai hâte de lire la suite.