Norway's spectacular Lofoten islands were the scene of an important but lesser-known mission by the Allied forces in World War II.

Nowadays, Lofoten is a huge draw for tourists owing to its stunning scenery and regular sightings of the northern lights.

If you’re planning a visit, spare a thought for the small part that the islands played in the war effort as you marvel in the beautiful surroundings.

The Importance of Norway in World War II

Norway was a neutral country during World War II but was considered very important to both sides. The port of Narvik allowed the Germans to transport iron ore – an important resource for the war effort – from Sweden without having to use the Baltic Sea, much of which would be frozen in winter.

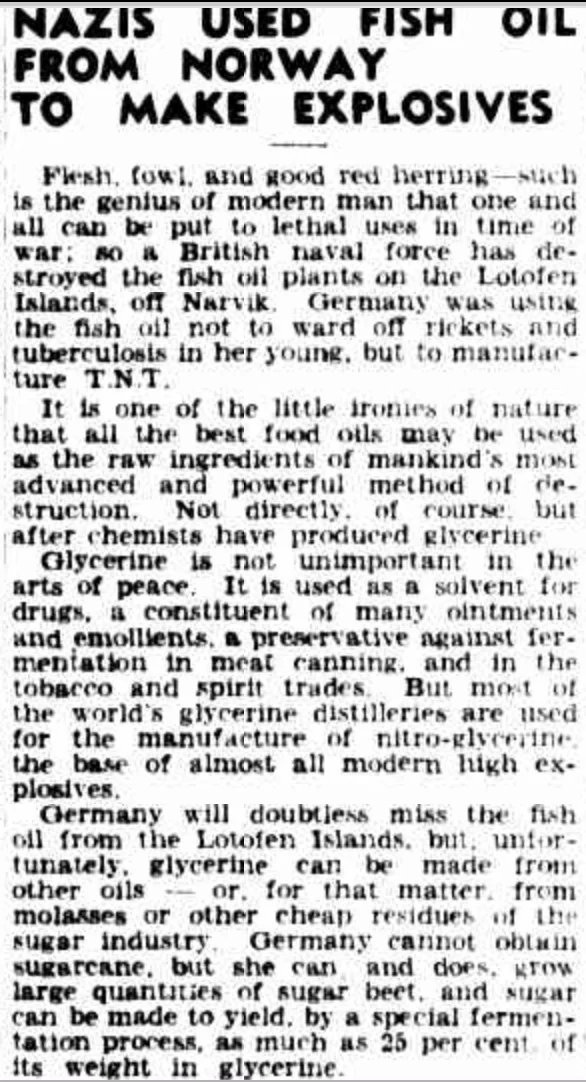

Also fish oil, which Norway produces in abundance, was useful to make glycerin that could then produce nitroglycerin to create dynamite. This newspaper clipping explains more:

For Britain and the Allies, as well as Norway being a country with some shared history and culture, it was vital to take hold of Norway purely to prevent Germany doing so. The main problem they had, with Norway’s neutrality, was finding a pretext to ‘secure’ the country.

The Allies developed Plan R 4, to secure strategic sites in Norway in the event that Germany violated Norwegian territorial integrity. The idea was to use mines to goad Germany into retaliation and then carry out Plan R 4 to prevent Germany from seizing control.

Germany, meanwhile, was developing Operation Weserübung to seize the country and protect its neutrality. This was sped up as response to the Altmark Incident, in which the Allies had liberated 299 prisoners of war from the German tanker Altmark which was sailing in Norway’s waters.

When the allies carried out Operation Wilfred, which planted mines in Norwegian waters to force German ships to travel in more exposed international waters, Germany felt it had sufficient excuse to invade Norway.

The Norwegian campaign

After Germany advanced through Norway, the Allies had no choice but to abandon their own plans and attempt instead to repel the invading force.

Britain had established a number of ‘Independent Companies’, drawn from the Territorial Army units, that were intended to take part in guerrilla-style operations against strategic German locations in Norway.

The campaign initially had some success and, along with the Norwegian army, were able to hold off Germany from Narvik for a few weeks. But with the Allied forces also being pinned back in France, leading to the Dunkirk Evacuation, the decision was made to retreat from Norway and the German occupation began.

Just 62 days after Germany had entered the country, a treaty of capitulation was signed. King Haakon VII, who had threatened abdication if the Norwegian government cooperated with the invading Germans, was exiled to Britain along with a large number of Norwegian troops who formed the Free Norwegian forces overseas.

The Allies strike back

Understanding the importance of Norway, and believing the withdrawal to have been a mistake, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill called for a new offensive force to be assembled, saying “…they must be prepared with specially trained troops of the hunter class who can develop a reign of terror down the enemy coast”.

Within three weeks, they had enough men and training to carry out their first raid, Operation Collar, which was a mostly reconnaissance mission in Northern France.

By November, more than 2000 men had volunteered for the commando units and they planned their first major offensive in Norway – Operation Claymore.

The Operation Claymore mission

Two commando units, a section of the Royal Engineers and the newly formed Norwegian Independent Company 1, were selected to carry out Operation Claymore.

The goals were threefold: Firstly, the naval flotilla of 5 destroyers were to escort the two landing ships safely to Lofoten and also destroy any German or Norwegian shipping vessels engaged in the war effort. They also had the task of providing gunfire support for the landing parties.

Secondly, the landing parties were to destroy as much of the fish oil industry as possible in the ports of Stamsund, Henningsvær, Svolvær and Brettesnes.

Finally, there were to engage the German garrison, attempt to take prisoners of war and detain any members of the Quisling regime, and persuade any locals to join the Free Norwegian forces.

Sailing from Scapa Flow in the Orkney Islands just after midnight on 1st March 1941, they refuelled in Skálafjørður in the Faroes before finally setting out across the North Sea, arriving in Lofoten on March 4th. The harbour lights were illuminated, which they took as a good sign that they had not been expected.

Read more: The Lofoten Islands

The landing force commenced their operations at 06:45 and were all on shore by 06:50. They managed to destroy Lofotens Cod Boiling Plant and two factories, destroying some 3,600 cubic metres of fish oil paraffin.

In total 228 prisoners of war were captured and the only opposition shots fired were from an armed trawler called the Krebs, which was quickly sunk, along with nine merchant vessels amounting to 18,000 tonnes of shipping.

Perhaps the most important part of the raid – an unexpected bonus – was the capture of a set of rotor wheels for an Enigma cypher machine along with its code books, taken from the sunken armed trawler. The machine itself was thrown overboard by the captain as the vessel sunk but the rotor wheels and codebooks were still highly valuable.

All of the landing force, along with the prisoners of war and 300 volunteers for the Free Norwegian forces, were on board the ships by 13:00.

Measures of success

Immediately after the operation, Winston Churchill hailed the raid as a success, issuing a memo “to all concerned … my congratulations on the very satisfactory operation”.

Part of the success was that it would tie up large numbers of German forces in Norway and, whilst Germany could no doubt access other sources of glycerin for dynamite, it would dent their abilities.

The Norwegian force, under Commander Martin Linge, were more doubtful about the value of the operation but, of course, they were not informed of the vital cryptographic information that had been gained.

The rotor wheels and codes could be used at Bletchley Park to read German naval communications throughout March, April and May, enabling Allied convoys to avoid concentrations of German U-boats.

Very very interesting.I had no idea this had occured!