Busloads of tourists rush to Norway's North Cape for a photo opportunity but are back on their cruise ships within the blink of an eye. I slowed down and met some of the colorful characters—human and animal—that call this remote corner of Scandinavia their home.

I strode out onto the North Cape clifftop at 11:45pm as the sense of anticipation in the crowd was reaching fever pitch.

Here I stood with travelers from all over the world, on a remote cliff at the edge of mainland Europe waiting for the clock to tick around to midnight.

As the moment came and went, the sense of anti-climax among the hoards was palpable. Oddly, my mind flew back to 1994 when the UK introduced its National Lottery.

For weeks it was all anyone was talking about but when the numbers were drawn, all but seven people were left wondering “that’s it?”

What now?

Back in the present, people hugged and kissed, took a photo or two, and then reality dawned.

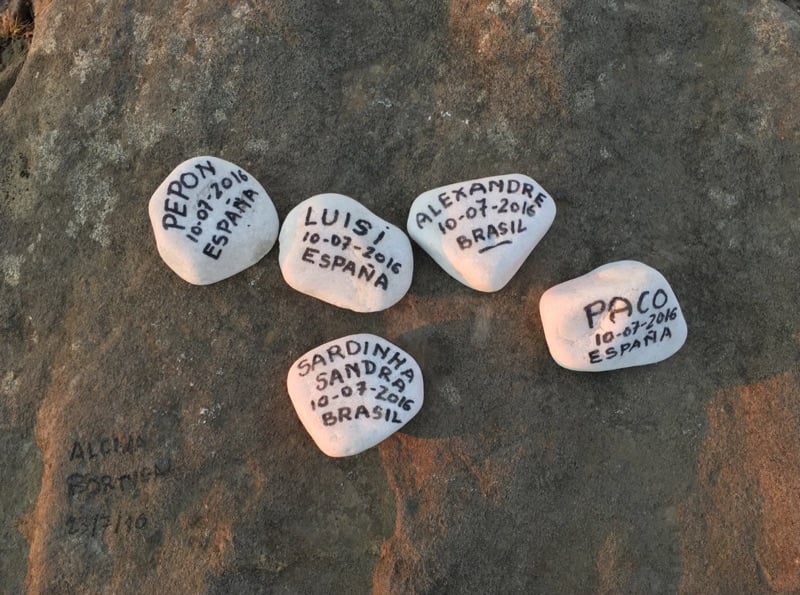

They’d paid a hefty fee to stand on a cliff top, with nothing else to do but scrawl their names on stones.

Unlike the northern lights, whose ribbons dance delicately across the winter sky, the midnight sun doesn't actually “do” anything. It hangs low in the sky at 11:45, it’s still there at midnight, and it’s still there an hour later.

Sure, there’s often an impressive orange glow, but there’s no light show, no fireworks, and no real sense of occasion.

Back inside the modern visitors’ center with what must be Norway’s largest gift shop, I recognized two friendly faces. A grandmother and her grandson, who I’d met three days earlier in Alta but had no idea they were making a similar journey as me.

We smiled at each other, sharing the secret that the hundreds of others rushing past us had missed out on.

Seeking something to do in Alta

My starting point for the journey, Alta, is not shy about pushing its self-awarded title of Norway’s “northern lights city,” but I couldn't help wondering why they pushed it so hard to people arriving at the height of summer, when seeing an aurora display is an impossibility.

Was this a coded way of saying there was nothing else to do?

A quick stroll around the city center—a soulless modern grid of a shopping mall, hotels and a curious building that I thought was a crematorium—revealed the answer was probably yes.

A closer inspection revealed the curious building was in fact the town’s church designed and named after, of course, the northern lights. But it was closed.

Meeting the Sami

It took merely seconds to decide to jump back in the car and find out where all the people were.

After parking up in a residential area and taking a pleasant stroll through a riverside campsite, I spotted the distinctive bright colors of the Sami flag.

The indigenous people of the northern Nordics, the Sami had fascinated me since I watched Joanna Lumley’s BBC documentary on the northern lights. I was soon in the company of an eccentric Sami gentlemen dressed in full traditional garb.

He makes his living by bringing his reindeer to Alta for four months of the year and charging tourists fifty kroner a time to feed them moss that he picked up off the ground and put in plastic bags. My new friend was a genius.

No sooner had I patted one of the reindeer than I was whisked off inside a lavvu, an authentic Sami tent, which he generously called a museum.

Rather than a curated collection of historic artifacts, this appeared to be a dumping ground for his personal possessions.

A very personal Sami museum

Item by item, he told a story of how it was used, why and by whom, before moving on to the long story about the Sami’s fight for recognition by the Norwegian government.

He was an expert storyteller, the kind of person who could spin a yarn about everything from reindeer antlers to the different kinds of moss (and he did both).

But with that storytelling ability came a burning desire to share those stories with more people, and so his attention drifted off to a large family with three kids. I don’t blame him, he could sense three impending sales of his bags of moss.

Before I departed, I promised to send the photos I had taken and he pointed me in the direction of a husky lodge on the edge of Alta. “You’ll get lots more stories there!”, he said with gusto.

It was the perfect time to visit the husky lodge as the last night’s guests had left, the accommodation cleaned, and the new guests yet to arrive. So the owner had time to walk me around the grounds.

Here I found beautiful wooden cabins shaped like tents with a see-through wall so in the winter you could watch for the northern lights while keeping warm. More entrepreneurial points for Alta!

As we approached the dogs, each and every one of them started to limber up and stretch their legs, hoping to be chosen for the day’s activity. To say these animals love to run is an understatement.

The owner went on to tell me about Finnmarksløpet, a well-known dog sled race. I pondered out loud if it was the husky version of a marathon. “You could say that. But this is many hundreds of miles.”

Once I’d picked my jaw up off the floor, I learned Europe’s longest dog sled race has obligatory rest breaks and veterinary checks and the winner completes the race in 5 to 6 days, weather permitting. My respect for these stunning animals clicked up a notch.

Glorious sunshine in Hammerfest

While not strictly on the way to the North Cape, Hammerfest was a tempting 50km detour.

Tempting because a writing hero of mine, Bill Bryson, had famously trashed the town in Neither Here Nor There, a book written in an age before low-cost airlines, internet booking sites, and social media.

“I wanted to see the northern lights. Also, I had long harbored a half-formed urge to experience what life was like in such a remote and forbidding place.”

Unfortunately for Bryson he chose to visit in the depths of a dark winter storm on a hunt for the northern lights, whereas I was fortunate to visit in the middle of a freak summer heatwave.

On the approach, I met a group of reindeer, not shy as I expected but casually strolling along the road as if my car didn’t exist. Yet when I got out of the car, off they ran.

What’s in a name anyway?

Guidebook duty compelled me to call in to the Royal and Ancient Polar Bear Society, which is essentially the gift shop of the tourist office that offers visitors the chance to “join” a society that is neither royal nor ancient.

Throw into the mix the fact that the nearest polar bears live 500 miles to the north across a freezing cold ocean, I found the name highly amusing.

Much to the chagrin of the Norwegian-English-German-French-Spanish speaking guide, I belly laughed when she handed me a membership form. I don't think I’ll be receiving an invite to the annual society meetings any time soon.

Before I left, a Russian sunbather who seemed to have a sixth sense that I was a guidebook writer said I simply had to visit the silver shop on the road to the North Cape.

I imagine a lot of people drive straight past what looks like a bit of a tourist trap, but in this barren landscape a blue wooden hut with sparkly things outside should grab anyone’s attention.

I wanted to chat to the owner, but he was hard at work in his workshop, which was simply an alcove within the shop. No cheap imports here, this guy made everything that was on show, and although the prices were expensive even for Norway, this made a refreshing change.

Their northernmost life brought to life

After a couple days of imaging how I would spend my time if I lived in such a place, the tiny village of Honningsvåg instantly won me over.

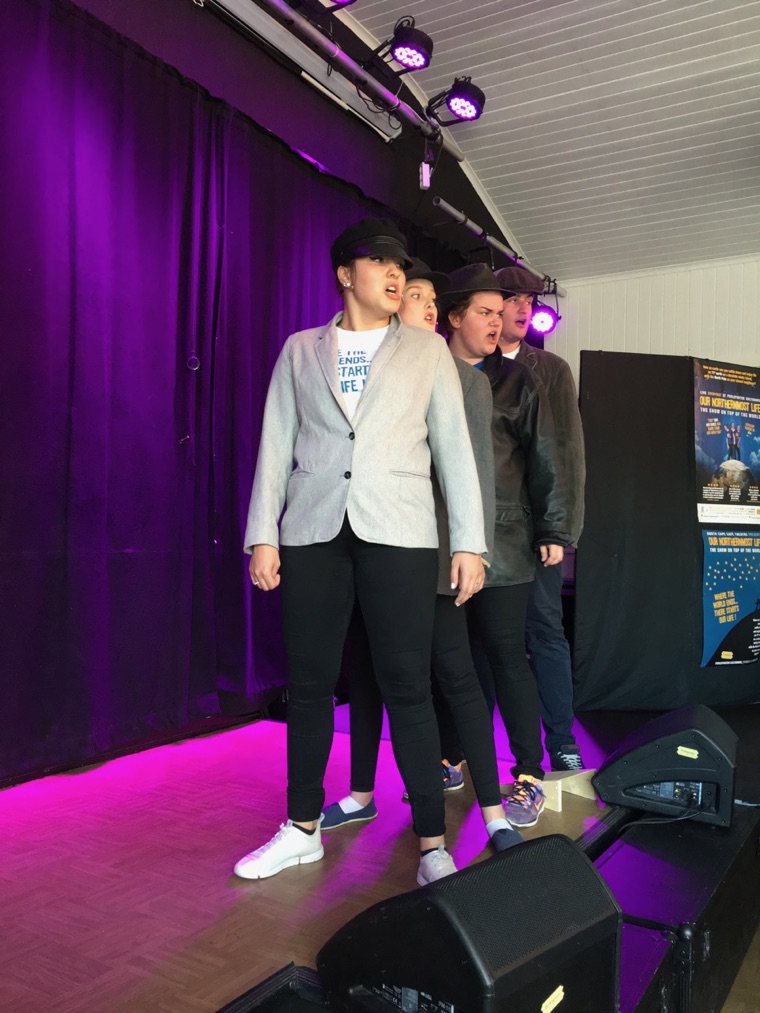

A handful of the town’s youths put on a daily performance of Our Northernmost Life, a genuinely funny am-dram musical about the difficulties and hilarity of living somewhere so remote.

The winter storms, the windy days, the French backpacker that missed her bus. “I’ll take you!” screams a local, delighted to have a reason to talk about Norway for an hour.

These kids might all flee to Oslo, Copenhagen or London in a couple years, but right now they are making the most of life in a remote Arctic village, and it almost made me want to move here. Almost.

After the show, I took a stroll around the deserted village and stunned the museum receptionist by wanting to actually see the museum. “We only get tourists from the cruise ship usually,” she said, seemingly wanting me to go away and come back with the masses.

So I did. I stepped outside, and there they were. The loudspeaker was the first clue. The cruise ship’s announcement echoed around the buildings of Honningsvåg, and the locals sprang into action.

Blackboards offering “cruise specials” sprung up outside every cafe, and postcards of the midnight sun blocked every sidewalk. One hour later, I'd seen hundreds of visitors file into the gift shop and straight back to the boat, with hundreds more boarding buses to whisk them off to the North Cape. And with that, the village fell silent once more.

The Midnight Sun is best appreciated on your own

There are no trees to be found anywhere on Magerøya island. As I drove north of Honningsvåg for the final leg of my journey, the barren environment just served to increase the feeling that I was heading for the end of the world.

Ignoring the magnetic pull to continue on to the North Cape, I instead peeled off to the right and into the tiny settlement of Skarsvåg. After checking in to a basic cabin, I grabbed a hiking guide from the kiosk and off I set in search of the midnight sun.

Just 30 minutes away is the rock formation Kirkeporten, a perfect place to enjoy the long summer evenings in the peace and quiet. The sun dips between a gap in the mountains, but never out of sight, and only a handful of people seem to know this place exists.

The contrast between this experience, and the one I’d experience at the North Cape the next night could not have been greater.

By the time I eventually made it to the North Cape and paid the eye-watering entrance fee, I’d already seen the midnight sun. I had met a whole host of entertaining characters—human and animal—that make their living from the opportunities that such mass tourism provides.

Without this cliff, the visitor center and the busloads of tourists, this corner of the Norwegian Arctic would be lesser for it.

This article was originally published in the September 2017 edition of Perceptive Travel, the excellent online narrative travel magazine.

You are amazing David, I am borned in Norway but live now in Montana USA, I wish I had known about Norway when I lived there. But at age 90 traveling is somewhat difficult. Thanks for what you do!

My husband and I have seen the play Our Northernmost Life when we were in Honningsvag a few years ago. The actors did a wonderful job and it was very funny. Recommended for anyone in the area.

I am really enjoying my weekly newsletter about Life in norway. While I do not have a personal connection to Norway, my Fiancee was born In Norway. After the death of his Father when he was only 9, he was sent to England to live with his Norwegian Uncle. So I am learning as much about his Homeland as I can about these fascinating roots that he has inherited. The articles are informative and interesting. Thank you