Known as the ‘Heavy Water War', it was the most successful act of sabotage in World War II. It took place right here in Norway.

Often-overlooked aspects of the Second World War are the actions of resistance movements across Europe. While Norway saw only a few major battles, the acts of resistance movements in Norway helped to hinder and even create an end to the occupation by the Nazis.

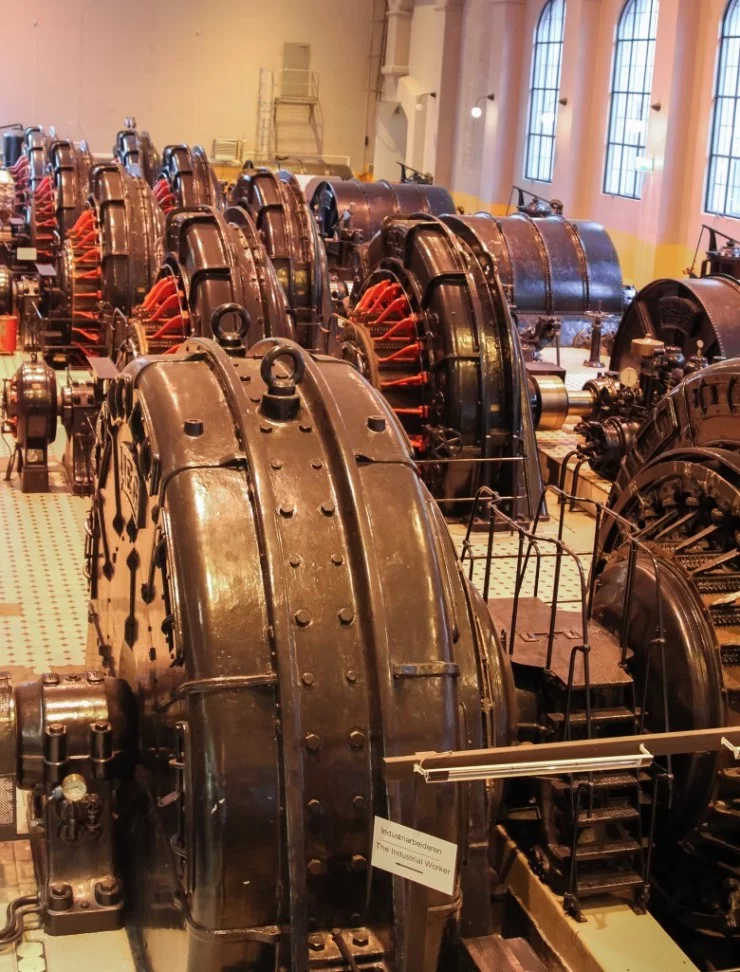

One such operation was Operation Gunnerside, which sabotaged the Vemork heavy water plant in the sleepy mountain village of Rjukan.

Heavy water

In late 1938, Lise Meitner, Otto Hahn, and Fritz Strassman discovered the phenomenon of atomic fission.

Physicists all across the globe realized that if chain reactions could be tamed fission could lead to a promising new source of power; others yet saw the potential for it to be used as a weapon.

What was needed was a substance that could “moderate” the energy of neutrons emitted in radioactive decay.

The heavy water (water in which the hydrogen in the molecules is partly or wholly replaced by the isotope deuterium), made at the Vemork plant was a prime candidate for the job.

One of the most interested parties in heavy water was Nazi Germany. It was discovered that the Germans were using heavy water from the Norsk Hydro plant, the only commercial production facility, in their atomic research program.

Wanting to keep an atomic bomb out of Hitler’s hands, allied forces deemed it imperative to take action in Norway.

First operation

The first plan to destroy the Vemork water plant was much like other strategies to destroy industrial targets during WWII, bomb it into oblivion using aircraft.

However, after a study of the plant, and inside information from its architect, it was determined that the sturdy, concrete facility perched on a steep hillside would not be an easy target to hit, or be destroyed by unguided bombing. It would have to be destroyed from the inside.

Eventually, a plan began to materialize. It involved a series of separate actions over a period of more than two years. The first of these was an insertion of a commando unity, codenamed Grouse.

On 18 October 1942, four Norwegians, recruited and trained by the British Special Operations Executive were parachuted into Norway.

Their primary missions were to reconnoiter the target and provide ground support for the people involved in the second phase of the plan. This second phase was the insertion of British Engineers and commandos via glider to assault the plant and destroy as much of it as possible.

Unfortunately the gliders and one of the bombers ferrying them to Norway crashed far from their intended landing site and the British troops and airmen that survived the crash were subsequently rounded up by the German Wehrmacht.

Operation Gunnerside

After this failed mission a new commando group made up entirely of Norwegians was formed; they created a similar plan of attack to the original mission; changing only the name to Operation Gunnerside.

In February, Operation Gunnerside delivered by parachute an additional six Norwegian commandos, along with weapons and supplies. After a few days of searching, the Gunnerside team linked up with the hidden Grouse team, who had been waiting for months in the Norwegian wilderness.

The joint assault force, using the cover of being students on a skiing vacation, reconnoitered Vemork from a safe distance and determined the best point of entry.

Then, late on a cold February night, the commando team climbed up the cliffs of the massive gorge below the plant, slipped in, set explosives that destroyed the heavy water inventory (about five months production) and production machinery, before quickly fading away into the surrounding mountains. They skied toward the border with Sweden.

A successful operation

The Gunnerside raid was a great success, an almost perfect commando operation that achieved its objectives with no friendly casualties. The action was cited by the British SOE as the most successful act of sabotage in all of World War II.

Yet the day was not won quite yet, while the plant was essentially destroyed it was quickly able to resume production of heavy water. The allies learned of a shipment of the substance to be shipped via ferry across the lake at the bottom of the valley from the plant.

Relaying this information to the Norwegian resistance fighters a plan was formulated to have several members of the organization ride the same ferry on its trip towards the Hydro plant, placing explosives onboard, before disembarking at Rjukan.

Once again, the operation was a success.

Referring to the sinking of the ferry carrying the heavy water: “Once again, the operation was a success.”

Yes, much more so than the Vormark raid.

However, you fail to mention the number of Norwegians that died when the ferry was sunk. The Resistance couldn’t warn anyone to avoid the ferry on that fateful day for fear of giving away the plan to sink it. Especially because they were unwitting participants, sacrificed for this critical effort, they deserve a mention in any writing about the Heavy Water War.

Damn :l

good for you to acknowledge this ….

You neglected to mention that the surviving British Commandos from the plane crash during the first attempt were all executed by the Germans.

Also omitted was mention of a bombing attack on the plant that killed a number of Norwegian civilians, halted production, and initiated the shipment.

Incidentally, the name Gunnerside was taken from a tiny village in Swaledale in Yorkshire, in northerne England. The leader of SOE, CJ Hambro, was married to the widow of the man who originally owned a hunting lodge in the area. Other codenames included Grouse as well as other birds in the area.

I saw a wonderful old movie, and then a documentary, about this called The Heroes of Telemark.

There is a 6h docuseries dedicated exclusively to this part of the norwegian resistance. Outstanding production and greatly accurate

Name of docuseries?

The The Saboteurs

2015 ‘Kampen om tungtvannet’ Directed by Per-Olav Sørensen

Why was heavy water being extracted at the Vemork plant in the first place?

Several comments are “you failed to mention this” “you failed to mention that” and I’m confident there would be no end to what would eventually become trivia. Sometimes it’s nice to read a concise summary of key events.