Born in Wales to Norwegian immigrant parents, Dahl grew up speaking Norwegian at home.

It was Welsh coal that brought Roald Dahl into the world, 100 years ago on September 13 1916.

That is, it was Cardiff – at the time the greatest coal port in the world – that tempted his father Harald to move from Paris in the 1890s to set up a shipbroking firm to service the world’s merchant fleets.

No one could claim that the young Dahl – who had a privileged, bilingual Anglo-Norwegian upbringing in positively palatial premises in Cardiff’s well-to-do suburbs – had hawser grease and coal dust in his veins.

The closest he got was playing as a child on the floor of his father’s offices down the docks.

But he is inescapably the product of the south Wales industrial boom. This fact, and his early experiences in and around Cardiff, and in exile from it, were processed by Dahl the writer in complex ways.

Wales is rarely present in Dahl’s work for children and adults in explicitly summoned forms, though he did put on record how important the land was to him.

Rather, Wales and aspects of Welshness are summoned indirectly in allegorical shades, echoes, embedded quotations, uncanny parallels and spectral absences, all of which are explored in a new book, Roald Dahl: Wales of the Unexpected.

Though there are pitfalls to reading Dahl’s work through the lens of Wales, the paradoxes and tensions of his Anglo-Welsh sensibility are present throughout his fiction.

Dahl’s perspective

His education, class, Norwegian heritage and upbringing in anglicised Llandaff largely insulated the young Dahl from the Welsh language, and even from the native Cardiff accent, for the nine years in which he was resident in Wales.

And yet he must have attuned himself to the frequencies of Welsh speech and to the distinctive shapes of Welsh culture. Indeed, these elements of diversity, and this perception of difference, would later condition his writing and social stance.

Dahl’s restless imagination sought always to relativise and triangulate any single cultural location and identity.

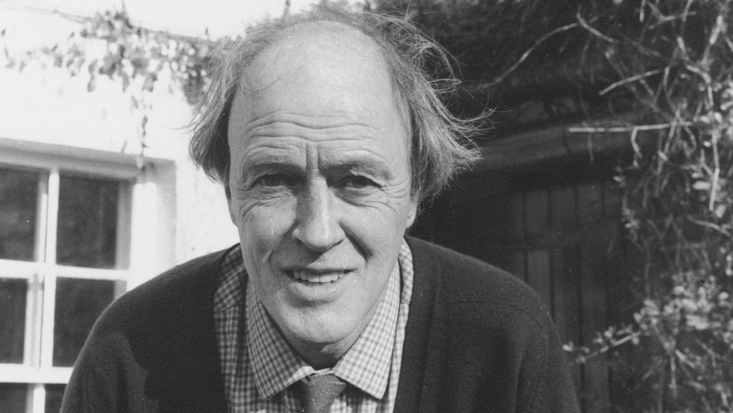

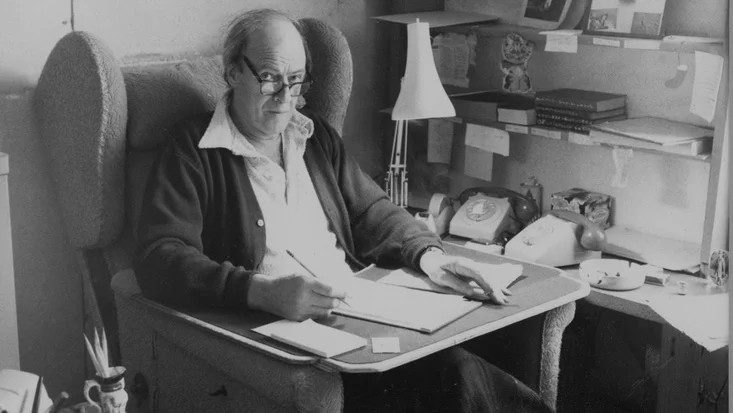

Dahl became an English countryman, regarded by the sniffy London literary set – whom he despised, but whose recognition he characteristically craved – as something of a “rural maverick”, working in a small hut in the Chiltern Hills of Buckinghamshire.

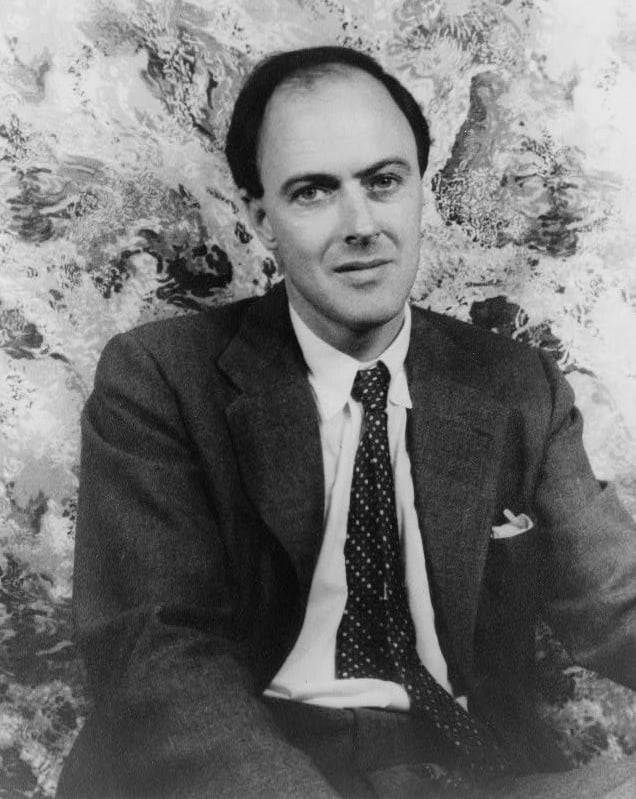

We can also speak meaningfully of Dahl as an American author: America kick-started his career, and his fiction for both children and adults betrays a bracingly unstable amalgam of Anglo-American tones and references. What, then, of Dahl as an Anglo-Welsh author? The category is a broad church.

After the untimely death of his first wife, Harald Dahl married a fellow Norwegian, Sofie Magdalene, and the family moved to the imposing pile of Tŷ Mynydd (Mountain House), Radyr, at the centre of an extensive farm estate. Dahl would seek to recapture the idyllic existence there among the fields – servants somewhere in the background – throughout his life.

It is a Welsh pastoral scene that underwrites the English landscapes of the books produced in the rural enclave of Great Missenden. The opening of James and the Giant Peach, for example, is emphatically the exiled Dahl’s cross-border view back to his parent’s house – as much Tŷ Mynydd as Gypsy House.

And yet, for Dahl, Wales was also deathly: a place not only of longing and delight, but also of loss, violence and the dark. Dahl told in Boy of orientating himself, by means of the Bristol Channel, to his Welsh home while at school in Weston-super-Mare.

This childhood longing is later haunted by the perspective of Dahl the killer, the trained fighter-pilot. His boyish desire for home replaced by a colder personality, deployed into foreign lands, trained to battle.

This is also a choice example of the ways in which reading his works for children in relation to his adult fiction – in this case, his tales of flying for the RAF in the early collection, Over to You (1946) – reveal the imaginative traffic between Dahlian worlds of innocence and encounters, and apparently incongruous categories of experience. It is a signature Dahl move.

The riddle of Roald

Homing back to Wales was always a paradoxical affair for Dahl, freighted with history and his own private pain.

As Dahl revealed in an autobiographical piece published towards the end of his life, the Dahls’ gardener at Cumberland Lodge, Llandaff – a man he called Joss Spivvis – used to regale him with an account of his first descent, at a tender age, down the shaft of a Rhondda mine in the pit cage.

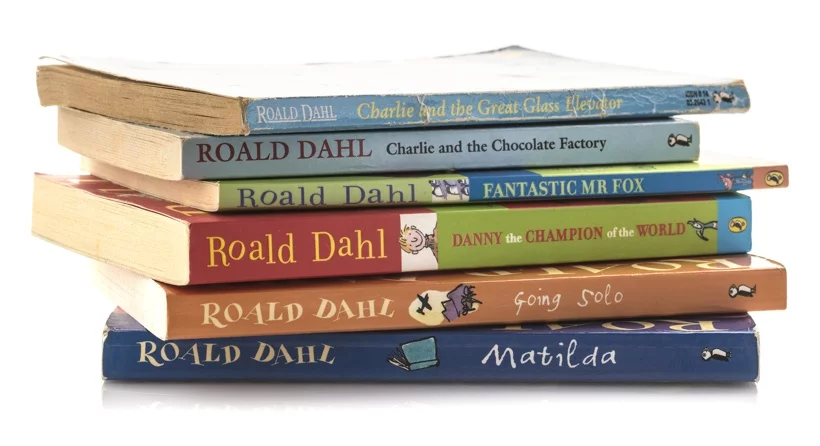

Fascinatingly, the description Dahl gives to Spivvis at this point maps uncannily onto the description of the descent of Willy Wonka’s great glass elevator in Charlie and The Chocolate Factory.

So at the heart of Dahl’s most famous fable is the terror of the Welsh industrial experience. What is at work here: a tired writer’s unavoidable recycling of material or an act of euphemism, as the proletarian experience is transformed into bourgeois fantasy?

Or rather – whether consciously or otherwise – a mark of belonging, an inscription of Welsh knowledge, of a Welsh individual’s personal testimony, a protest against all capitalist regimes?

Charlie and the Chocolate Factory can be read, with a salutary measure of Dahlian layered irony, as a Welsh industrial novel. Further, The BFG can be seen as the narrative of an outsider: one who inhabits margins and shadows, moving to the centre of cultural power and value.

The book also documents a linguistic trajectory, from the “terrible wigglish” the BFG used to speak (a hybrid, creatively yoking language) to “proper” cadences and to feted authorship. Glimpsed here is Dahl’s troubled reflection on his own move away from Wales, from perceived margins to English centres of culture, to which he never quite got access.

Wales does not solve the riddle of Dahl. But admitting Dahl’s Anglo-Welsh experience into our analysis and enjoyment of his work adds to our understanding of this master of conflicted, paradoxical worlds.

This article was written by , Professor of English Literature at Cardiff University, and was first published by our friends at The Conversation.