One of the biggest natural disaster risks in Norway lies beneath our feet. Quick clay landslides are a truly terrifying threat. Here's what you need to know.

Images of the recent Gjerdrum landslide shocked the world. But it was far from the first such incident in Norway involving quick clay.

Quick clay–known as kvikkleire in Norwegian–describes a special type of clay, which, when overloaded, can liquefy and collapse. The results can be disastrous.

What is quick clay?

Quick clay is found primarily in Norway and Sweden, but also exists in parts of Finland, Russia, Canada and Alaska. To find out more about what it is, we turned to our friends at the Norwegian Geotechnical Institute, NGI.

Quick clay is found below the marine level (the present elevation of where the sea level was at end of the last ice age) in Scandinavia.

As the historic ice masses melted, the small clay particles flowed with the water and sedimented in the marine environment in salt water along the coastline.

As the ice melted, the land slowly rose. Clay previously situated underwater was now elevated above sea level. Salt in the clay layers has since been washed out due to fresh groundwater. This drastically changed the strength characteristics of the clay.

If such clay is overloaded due to natural causes or from man-made action, the clay mass can instantly liquefy, causing the land to slide. This can spread over large areas, causing structures at ground level to collapse and/or float over considerable distances.

Notable quick clay landslides in Norway

Many incidents occur in Norway. However, some are more notable than others.

1893: Verdal

On a spring night, Verdal was struck by the most severe quick clay slide on record. 55 million cubic metres flowed out and flooded the town. A total of 3 km² of surface area was destroyed, including 105 farms. 116 people lost their lives.

1978: Rissa

Despite noone being killed, the Rissa landslide is one of the country's most famous because it was the first to be captured on film.

Two local teenagers captured an 8mm film of the initially minor landslide, which soon propagated over a much larger area. Overall, 6,000,000 m² of clay slid into the inner fjord Botn, causing a small tsunami to strike a neighbouring village. One person died.

2012: Byneset, Trondheim

A soil slide several hundred meters long struck a creek at Byneset in Trondheim municipality. There were no casualties, but 50 people were evacuated for several days.

2020: Kråknes, Alta

This landslide was triggered by the combination of heavy snowmelt and 80 truckloads of stone to be used in construction. That's the verdict of the official report into the incident, in which 900,000 m² of clay took 8 properties into the water.

The owners of a cabin received permission in 2015 to erect a 33 m² extension, but then proceeded to pile up 80 truckloads of stone.

“It is a development that has contributed to reducing the stability in the area so much that the landslide could go, when the stress from snowmelt and water became large enough,” said NVE's Knut Aune Hoseth to NRK.

Remarkably, no lives were lost. Most of the properties were cabins and/or secondary homes.

2020: Gjerdrum

A few days later Christmas, several houses were taken by land movement in the middle of the night on the edge of the village of Ask in Gjerdrum municipality. More than 1,000 people were evacuated, but ten people sadly lost their lives.

“I have forest in the garden that was not there before. It is a bit difficult to describe,” said an eye-witness who lives approximately 200 metres from the site of the major landslide.

The risk of future landslides

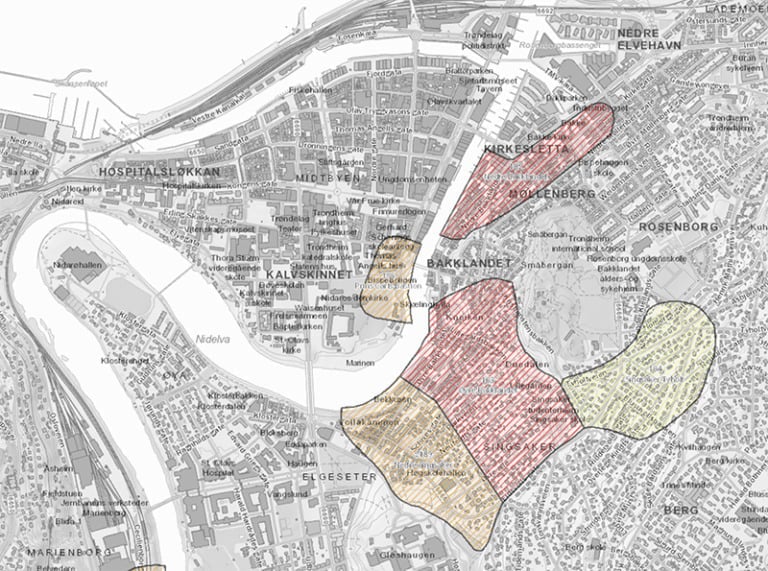

According to the Norwegian Directorate for Civil Protection (DSB), quick clay constitutes a “significant hazard” in large parts of the country. In a disaster planning report, DSB outlined a scenario for a quick clay landslide in a city, specifically in the Bakklandet neighbourhood of Trondheim.

DSB estimates the likelihood of the Bakklandet scenario at 4% in the next 100 years, one of the lowest scenario likelihoods in the report.

However, the nationwide likelihood of such an incident (a quick clay landslide in a city) is estimated at 35% in the next 35%, a much more worrying prospect.

Aside from Trondheim, the Norwegian Water Resources and Energy Directorate (NVE) maintains an overview of nine other densely populated areas where quick clay is a similar risk.

Rules and regulations are in place for surveying vulnerable quick clay zones, especially ahead of planned construction or other significant activities. The guidelines for building are available here, in Norwegian.

Do I live on quick clay?

Yep, it was the first question I had too after I saw the devastation caused by the Gjerdrum incident. Even more so when I discovered that Trondheim has several high-risk areas.

NVE offers an online map of risk areas, which you can access here. However, the work is ongoing, so your area may not have yet been surveyed. The priority areas of Trøndelag, the Oslofjord region and large parts of northern Norway are available.

Arter Gjerdrum sliding l have been a message to life Norway .İt was about that l have been mentioned that Geolojical surway before must be done to build houses for allow construction.Yes you have very good Technical Sturucture.İ know a little Geology because of my education our İstanbul Tech.Üni.(İTÜ) during my Metallurg ical Engineering ,Mining Metallurg Faculty.İ must repeat again for disaster s possibilities anywhere must subject investigation Survey ground for costuction you have very good capabilities.And risk maps must be made .