An introduction to the fascinating life and experiences of Norwegian polar explorer Otto Sverdrup.

Over the years, Norway has supplied many of the world's explorers, especially to polar regions. It's the main reason why today Norway lays claim to Svalbard in the high north and parts of Antartica in the far south.

When we think of Norwegian polar explorers, names that come to mind are usually those of Roald Amundsen, first man to reach the South Pole, and Fridtjof Nansen, leader of the first polar drift expedition.

But Otto Sverdrup did more than enough to deserve a place of honour next to those two.

So let’s look at the life of Otto Sverdrup, his accomplishments, and the possible reasons for why he never really got the recognition he deserved.

Otto Sverdrup’s early life

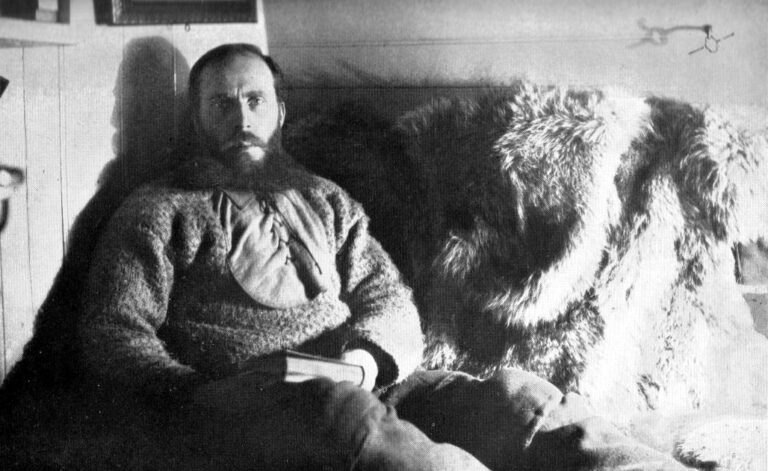

Otto Sverdrup was born in 1854 on a farm in Bindal in Nordland county. As a child, he and his elder brother were homeschooled by their grandfather.

He liked to go on adventures with his brother, and they both loved hunting. He is said to have shot his first bear at the age of 14.

He left his hometown when he was 17, and worked as a sailor for three years. When he returned, he took the required exams to become a helmsman, and went on to study in Trondheim, for two years, in preparation for his certification as a skipper.

He then started his career as a helmsman on various ships in Norway and the United States.

Meeting with Nansen

In 1887, Fridtjof Nansen was assembling a team to cross Greenland by ski – a feat that had never before been accomplished. Sverdrup heard of this and became determined to participate.

He managed to get an interview with Nansen's brother, who he sufficiently impressed to secure his recommendation that he be hired for the trip. At this time, he was 33 years old.

Little was known of Greenland at the time. Some scientists thought there was a chance that the middle of the island might be inhabitable.

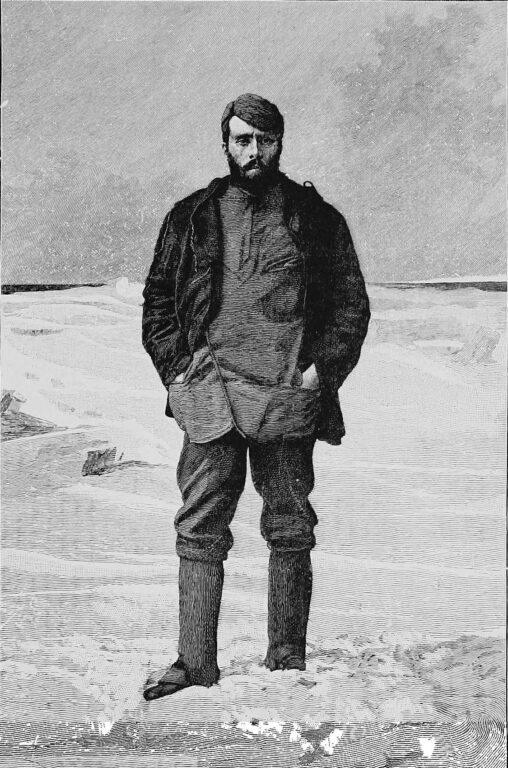

A crew of six was assembled, including Nansen and Sverdrup, and they set out on a seal hunting ship in the middle of July 1888. After a difficult journey of about a month, they finally made it to the east coast of Greenland.

Skiing across Greenland

They set out westwards on skis on August 15th, 1888. They reached an altitude of 2,720 metres on the ice sheet and dealt with difficult weather conditions.

On September 26th, they finally reached the west coast of Greenland, or rather, the inner part of a fjord. They still had a long way to go to reach Godthåb (today known as Nuuk, the capital of Greenland) so they decided to build a boat.

Trees are scarce in Greenland, but there were in many places along the shore two metre high thickets of willow and alder, which they somehow managed to use to build a boat. They used bamboo poles they had brought with them to build the frame and branches for the ribs.

They then stretched out a piece of fabric that had until then been the tent floor and sewed it into place as a hull of sorts. The rudimentary vessel was not much to look at, and not terribly easy to manoeuvre.

The boat could only fit two people, so it was decided that Nansen and Sverdrup would set out for Godthåb and send for the remaining four explorers. It took the pair four days to reach a shore that was inhabited.

As planned, they sent kayaks and supplies to the rest of their party, with whom they were reunited a few days later. Meanwhile, they learned that the last ship before the winter had already sailed a while ago, and that they would have to spend the winter in Godthåb.

That time spent with the local population proved invaluable to the polar explorers. They got to learn from the wealth of knowledge accumulated by the Inuit over generations, about clothing, food, and not least how to use dogs to get around.

They returned to Kristiania on May 30th, 1889, and were awaited on the dock by thousands of people.

The polar ship Fram

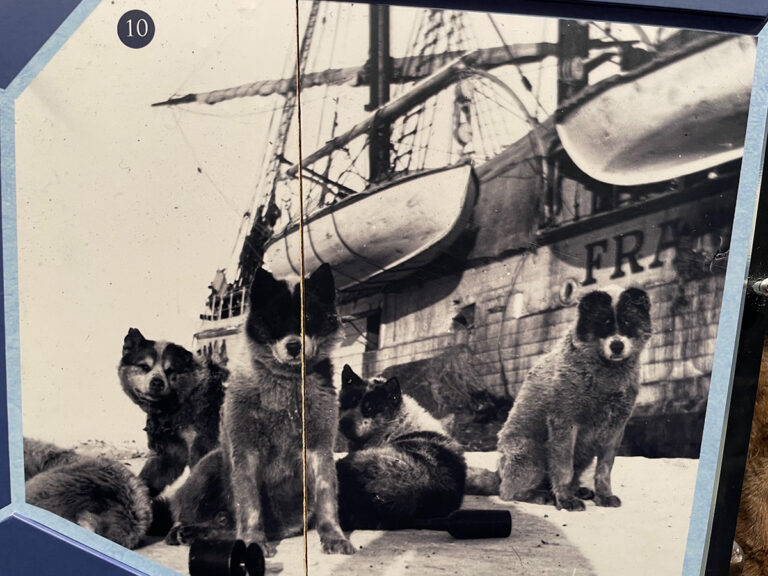

Nansen was so impressed with Sverdrup’s stamina, wits and practical mind that he hired him as a consultant during the building of his polar ship Fram, in 1892. Sverdrup supervised the building of the ship, which had a unique design.

The ship’s hull had rounded sides and hardly any keel. This allowed it to rise up over the ice and then come back down without getting stuck.

This is how icebreakers are designed even today: with a rounded hull that allows them to slide on top of the ice – though in the case of icebreakers the ice then gets crushed under the enormous weight of the vessel.

The design was groundbreaking at the time, and many sceptical observers regarded the expedition as doomed. No one had actually entered the Arctic ice before, and the fear was that the ice would simply crush the hull.

The ship’s hull was very thick, with multiple layers of wood and felt, which allowed its occupants to keep warm despite the freezing temperatures outside. The outer part of the hull was made of greenheart, a South American tree that is twice as hard as European oak.

The Fram was also equipped with a variety of scientific equipment, which allowed Nansen and his team to conduct research and collect data during their expedition.

First Fram expedition

Otto Sverdrup was chosen by Nansen as captain for the first Fram expedition, which left Kristiania on midsummer’s day 1893. It took three months for the ship to get into the ice, to the point where it froze in and started drifting.

Nansen’s hope was that the drift would bring him directly above the North Pole, but this did not happen. The ship still set a record though, reaching a formidable 85 degrees and 59 minutes of latitude.

The Fram came out of the ice on August 13th, 1896, after three long years away. The North Pole had not been reached, but Nansen, Sverdrup and their crew had proven that it was indeed perfectly possible for a ship to drift with the polar ice and come back out in one piece.

Back in Kristiania, a crowd of 60000 gathered to welcome the expedition participants. They were all invited to dinner by the King of Sweden and Norway, Oscar II.

Second Fram expedition

After the resounding success of the first expedition, financing a second one proved to be an easy task. The Fram was taken to the shipyard and an extra deck was added, which markedly improved living conditions onboard.

This second expedition would focus on science, with topics such as zoology, geology, botany, cartography and meteorology being in focus. On midsummer’s day 1898 the Fram left Kristiania with 16 men onboard, and Sverdrup in the lead.

The main goal of the expedition was to map the northernmost part of Greenland, as well as some blank spots on the east coast of the island.

On the 18th of August, the ship got stuck in ice near the coast of Ellesmere Island, Canada’s northernmost island. The ship would spend the next year in that area, with expedition participants spending their time mapping unknown areas and collecting scientific data.

Most members of the expedition fared relatively well, living on a diet of muskox and polar bear, but for the expedition’s doctor, the difficulties of life in the Arctic wilderness proved too much to bear. He shot himself in June of 1899, leaving behind a letter stating that this kind of life was not for him.

Despite this tragedy, the expedition would carry on for a total of four years. The data collected during the trip would lead to the publication of 35 scientific papers.

Maps produced during the trip were of such a quality that Canadian authorities were using them until the 1960s, when satellites made it possible to generate better ones. Three large islands, Axel Heiberg, Amund Ringnes and Ellef Ringnes, were mapped and named after three businessmen who financed the expedition.

A break from polar exploration

After his return to the mainland in 1902, Otto Sverdrup started working on his account of the expedition, a two-volume work published in 1903 under the title Nyt Land (English version: New Land).

The following year, he went to Cuba to try something altogether different.

He ran a plantation in the eastern part of the country, near the town of Baracoa. He had plans to grow bananas, cocoa and coffee, but bad weather conditions meant that the venture resulted in failure.

He then tried setting up another business: seal and whale hunting off the coasts of Greenland and Alaska. This too, failed.

Return to the Arctic

In 1914, Sverdrup was called upon by the Russians to help locate three missing Russian Arctic expeditions. He captained a ship called the Eclipse, and set course for the Kara sea.

The missing expeditions were never found, but Sverdrup rescued two naval transport ships transporting a total of 80 men, which were stuck in the ice. Some of the stranded crew were brought over to the Eclipse, while others were rescued later.

Sverdrup’s legacy

There is no doubt that Sverdrup is the least known of the “big” Norwegian polar explorers. It seems that this is not due to his lack of ability in the field, but to the fact that others like Nansen and Amundsen were better at self-marketing.

Sverdrup's relationship with Fridtjof Nansen was complicated. They worked well together during the Greenland voyage, but Nansen's heavy-handedness and penchant for isolation took their toll on everyone during the first voyage on the Fram.

In 1897, Nansen accused Sverdrup of going behind his back when raising funds for the second Fram expedition. Sverdrup believed that he had received too little money for his contribution to the first voyage.

Towards the end of his life, the two were reconciled. In 1926 Nansen took him on his triumphal journey to St. Andrews University in Scotland, where Nansen was named honorary rector, and Sverdrup himself received an honorary doctorate.

Today, Otto Sverdrup has a moon crater named after himself, as well as a frigate of the Royal Norwegian Navy and a Hurtigruten Expeditions ship.

Fram, the ship captained by Sverdrup, can be viewed at Oslo’s Fram museum. It is one of the city’s top museums and well-worth a visit if you are at all interested in polar exploration.

You should do an article on Bjorge Ousland, first explorer ever to solo to the North and South poles, and circumnavigate the Artic. Still alive, near Oslo.