Sometimes, a spur of the moment action by a single person can end up saving hundreds of people. This is the story of such an action, and the hero of this story is a 15 year old Norwegian boy named Martin.

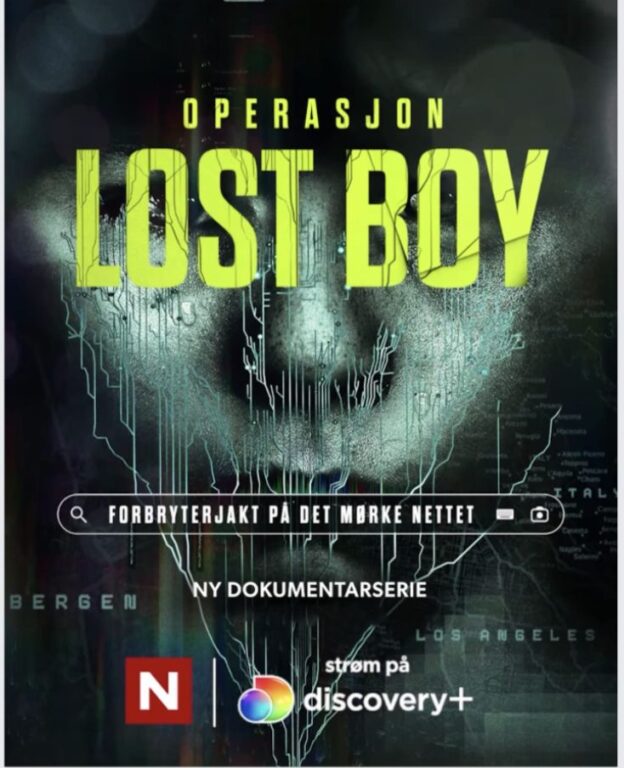

His actions led to the dismantlement of a huge international child molestation network that had ramifications across Europe and all the way to Hollywood, California. A five part documentary that was released recently sheds light on these events.

Operation Lost Boy reveals a network that operated in the US, Canada, Brazil, Belgium, France, Italy, Germany, the UK and New Zealand.

Join us as we review the documentary and expose how the quick thinking of a single boy in a bad situation helped send dozens of paedophiles to prison.

Disclaimer: there are spoilers ahead so be warned if you plan on watching the documentary. Be aware also that some of the events described in this article are disturbing.

Bergen, Norway

The story starts in Bergen in 2006, with a 15 year old boy named Martin Krossnes. Martin thought he was on his way to the centre of town to meet a boy his own age he had been chatting with online.

When he arrives at the agreed meeting point, he quickly realises that the person he had been talking to is a man in his late thirties. Bewildered and unsure what to do next, he agrees to follow the man to his hotel room.

Luckily, on the way there, he has the presence of mind to find a pretext to leave the man. Martin tells the man he needs to buy something and disappears into a nearby convenience store, where he calls the police.

Two officers arrive and drive him around to locate the man, without any luck. “Do you have any more information about him?” they ask Martin.

“I have his phone number and I know what hotel he’s staying at,” the boy replies. The police, looking up the phone number, are shocked to find out that it is registered as belonging to the Bergen police station.

They go to the hotel to confront the man, who turns out to be Johan Martin Vie, a police officer working in the Hordaland police district (the same district Bergen is a part of), in a small town called Odda. The man claims it was a simple misunderstanding; he thought Martin was much older than 15 years old.

Through questioning the man and seizing his computer, the policemen get a distinct feeling that he has something to hide, and find evidence that he has been looking for child pornography online.

But forensic analysis of computers is not yet very common in the country at this point, and a large backlog means the computer does not get analysed before a whole year has passed.

When they finally get to it, police find damning fragments of chats and images on the computer, showing that Johan Martin Vie was indeed sexually interested in children, and was in contact with other men sharing that interest. The chats are incomplete, but they paint a very damning picture.

Milan, Italy

Incomplete chat fragments found on Vie’s computer are sufficient for the police to establish that Johan Martin Vie previously travelled to Milan, Italy, to meet a paedophile friend he had chatted with online. They show that he has been fantasising with his online friend about sexual encounters with young boys in poor countries.

What’s more, by cross-referencing chat records and passport information, police can trace back his movements. At this point, Norwegian police need to act fast. If they want to convict their man, they need hard evidence.

To get this evidence, they need to track down the people he has been chatting with before they realise what’s happening and destroy the evidence. Through Eurojust, a European agency facilitating cooperation between European countries’ police forces, they get help from Italian police.

Investigation by the Italian police lead them to the apartment of “Guido”, a mild-mannered computer engineer in Milan who breaks down as soon as he sees the police. In that apartment, officers seize hundreds of thousands of images and videos of sexual assaults on children.

Gradually, the picture becomes clearer. Guido is aware that what he has been doing is wrong, and unlike Vie, he feels a need to confess everything and collaborate with the police.

The trove of data the police seizes allows them to paint a much clearer picture of the events. Fragmentary chats are now complete, and evidentiary images are innumerable.

Norwegian police quickly come to an unsettling realisation. Yes, this wealth of evidence will help them convict their man, but it also reveals the criminal activities of a very large number of people in many countries around the world.

Constanta, Romania

Some of the images involving Vie are traced back to Romania. To convict Vie, Norwegian police need to locate victims and get them to testify.

Romanian police successfully accomplish the needle-in-a-haystack task of locating a specific apartment in which a series of photographs have been taken. By comparing pictures on official databases with the seized images, they figure out the identity of several victims.

A picture emerges that shows Vie was using money to convince young boys from poor areas to let him take naked pictures of them. Once contact was established and he got them in the same room as him, he did other things to them.

The process of securing the evidence to convict Vie is fraught with complications. Romanian police follow local law, but Norwegian police have to make sure interviews are performed in a way that is compatible with Norwegian law so that they can be used as evidence.

Another complication is the human aspect of having the victims relive the events by recounting them – in front of their parents, no less. Unfortunately, it’s a necessary step to ensure the criminal is put behind bars and does not hurt any more children.

Kabul, Afghanistan

Another of Vie’s contacts revealed in chat rooms that he was working for USAID in Kabul. He was describing particularly grotesque sexual assaults in his chats.

Through a stray email address given by the man in a chat, police manage to figure out his real identity. This is when Norwegian police decide to involve the FBI, which prioritises the investigation.

Enquiries by the FBI reveal that the man, Sohail Ayaz, no longer works for USAID. As such, the FBI no longer has jurisdiction over him.

After further investigations, Norwegian police find out that the man now lives in London and works for international NGO Save the Children. English police get involved and the man is arrested.

He is sentenced to four years in prison in the UK, and ends up being deported to his native country, Pakistan, after serving his sentence. He is now on death row in that country.

Hollywood, California

Two of the men who Vie communicated with lived in California, and had been discussing in the chat room the logistics of going on a sex tourism trip to Europe to rape young boys. Evidence about those men was found in the material seized in Milan.

The FBI gets involved and finds out that the two men are Harout Sarafian and Woodrow Tracy. Through their surveillance, the FBI has reason to believe that Harout Sarafian’s computer is encrypted, and needs to be seized while he is logged on.

In other words, police have to make sure he walks away from his keyboard without logging off. They devise a stratagem by which they make sure through surveillance that he is online, and send a tow truck at that moment to pretend they are taking away his car.

As soon as he opens the front door to see what is going on, police handcuff him, and are able to access his computer and all the evidence it contains. Like in Milan, police seize enormous amounts of evidence.

Many lives changed

The operation, called Lost Boy, resulted in the indictment of 19 offenders in the US and 14 in other countries. Over 200 victims were identified. 50 new investigations were launched in the wake of the operation.

Johan Martin Vie is still in prison as a result of his crimes. His sentence was recently prolonged after a court found that years of therapy have not helped, and that he still poses a danger to young boys.

Our verdict

The documentary Operation Lost Boy provides a good overview of a complex story. It gives insight into the difficulties of working across international borders to secure the necessary evidence to convict criminals.

Like many other multi-episode documentaries, it tends to stretch the material a bit. What was covered in five episodes could have been wrapped up in two or three.

That being said, it is well worth a watch.

In Norway, Operation Lost Boy is available on streaming services Discovery+ and HBO Max. In Europe, it's on HBO Max and Amazon Prime, depending on your location. At the time of writing, it is not available for streaming in the US.