Interested in Norse mythology and don’t know where to start? We’ve got you covered! Here’s everything you need to know about the basics of Norse mythology (plus a little more).

Norse mythology is full of fascinating stories and complex characters. It’s no wonder that it has seen a resurgence in popularity in recent years, from Marvel’s Thor movies to Neil Gaiman’s American Gods (the book and the TV series) to Rick Riordan’s Magnus Chase series.

However, despite their popularity, the original myths remain shrouded in mystery, with debates raging on what certain events mean, who wrote what, and even whether the stories are the same ones that the Vikings told.

Therefore, we decided to collect all our articles about Norse mythology into one place in order to give you a basic rundown of the characters, events and locations, and their historical context.

Consider this guide a sort of Mead of Poetry (but better because no one died while writing this, and you don’t have to drink anything that Odin vomited up while he was a bird… yes, that is a thing that happened).

Table of Contents

Introducing Norse mythology

The story of Gylfaginning begins with King Gylfi of Sweden travelling to Ásgarðr (Asgard) disguised as an old man named “Gangleri” to ask the Æsir questions about the universe.

He meets Óðinn (Odin), who is also disguised and presents himself as as three kings named “Hárr” (High), “Jafnhárr” (Just-as-High) and “Þriði” (Third). Gylfi asks permission to ask his questions and Odin replies:

“Stand forward while you inquire;

The one who recounts shall sit.”

While we won’t insist that you stand while reading this blog post, we will hopefully answer any questions that you may have about Norse mythology.

Creation: “Early of ages, when nothing was…”

In the beginning, there were only two realms: Niflheimr (Niflheim), the realm of mist and ice, and Múspellsheimr (Muspelheim), the realm of fire. Between them was Ginnungagap, or the void. Where the heat and cold from these two realms met, steam was created, which collected in Ginnungagap and eventually created Ymir, the first jötun, and Audhumla, the first cow.

Read more: Norwegian Mythology & Folktales

Since these were the first two beings in existence, life must have been a little boring for them. Ymir would pass the time by drinking Audhumla’s milk and Audhumla would lick a salt block, which eventually took the form of Búri, the first of the Æsir.

Búri had a son named Bor, who in turn had three sons: Odin, Vili and Vé. These three brothers then killed Ymir and used his body to create the universe.

The nine worlds of Norse mythology

The Norse universe consists of nine worlds. These worlds are only referenced a few times throughout the myths and are not specified, but are thought to be (in no particular order) Asgard, Vanaheimr (Vanaheim), Jötunheimr (Jotunheim), Niflheim, Muspelheim, Álfheimr (Alfheim), Svartálfaheimr (Svartalfheim), Niðavellir (Nidavellir), and Miðgarðr (Midgard) – which is our world.

These worlds are connected by a great ash tree named Yggdrasil, which runs through the centre of the universe. An eagle lives at the top of Yggdrasil, while the dragon Niðhöggr (Nidhogg) lives at the bottom and chews on its roots. The squirrel Ratatosk runs up and down Yggdrasil’s trunk, carrying messages between these two creatures – and they’re not particularly nice messages either.

View this post on Instagram

In addition to holding everything together, Yggdrasil is also a source of wisdom and is where the Æsir often gather for meetings. At the foot of the tree is Urðarbrunnr (Urd’s well), which is associated with the three Norns or “fates”.

Under another root is Mímisbrunnr (Mímir’s well), which is where Odin gave up his eye as payment for a drink in order to gain the well’s knowledge. It is also thought that Yggdrasil is the tree that Odin hung himself on, again in the pursuit of knowledge.

The Norse Gods

There are two tribes of gods in Norse mythology: the Æsir and the Vanir.

The Æsir are the main gods in Norse mythology and live in Asgard. Notable Æsir include Odin, Þórr (Thor), Frigg, Heimdall, Týr, Bragi, Iðunn (Idunn), Baldr, and Loki (though not always).

Not much is known about the Vanir other than that they live in Vanaheim. Notable Vanir include Njörðr (Njord) and his two children, Freyr and Freyja, who came to live in Asgard as hostages to ensure peace following the Æsir-Vanir war.

Despite being hostages, Njord, Freyr and Freyja are quickly accepted by the Æsir. Freyja and Odin even split the souls of dead warriors between them, with half going to Freyja’s meadow, Fólkvangr, and the other half going to Odin’s halls, Valhalla.

Who goes where is decided by the Valkyries, who collect the souls of those “lucky” enough to have died in battle and carry them to their destination.

The Monsters of Norse Mythology

The Æsir and the Vanir may be gods, but they rarely behave well or honorably. Similarly, while this section is entitled “Monsters”, not all the creatures described here commit monstrous acts.

Aside from the Æsir, the other main group of characters in Norse mythology are the Jötnar, who live in Jotunheim. Jötnar is often translated as “giants”, but this is misleading as the majority of them are human sized.

Some Jötnar are exceedingly beautiful and some are terribly ugly, and the Æsir spend most of their time either fighting the jötnar or marrying them. Notable Jötnar include Skaði (Skadi), Gerðr (Gerd), Surtr (Surt) and Ymir.

Loki may also be classified as a Jötunn, as his father was a Jötunn, and Norse mythology is patrilineal, which means that membership to a family or group is decided through the father. However, the topic is not without debate.

In addition to the Jötnar, are the Ljósálfar (Light Elves) who live in Alfheim and the Dökkálfar (Dark Elves) who live in Svartalfheim. Little is known about the Light Elves, but “Dark Elves” may be another name for the Dwarfs, who also live in Svartalfheim.

The Dwarfs are said to have been made from the maggots that ate Ymir’s dead flesh and live underground in the darkness. This portrayal of the Dwarfs is not particularly flattering, but what they lack in beauty, they make up for in their skill in blacksmithing and crafting.

The Dwarfs are responsible for creating some of the Æsir’s most valuable possessions, including Mjölnir (Thor’s hammer), Gleipnir (the chains that bind the Fenris-wolf), and Sif’s golden hair after Loki shaved her bald off as a joke.

However, while the Dwarfs are very useful to the Æsir, the Æsir do not value them as equals and are in conflict with them as often as they are in need of their help.

Read more: Creatures in Norse Mythology

Ragnarök: The Twilight of the Gods

It is a common misconception that Ragnarok is the end of the world. Rather, it is the end of the current world order – although this does not make it any more pleasant to go through. According to the völva in Völuspá:

“Brothers will fight,

bringing death to each other.

Sons of sisters

will split their kin bonds.

Hard times for men,

rampant depravity,

age of axes, age of swords,

shields split,

wind age, wolf age,

until the world falls into ruin.”

The Æsir don’t fare much better: Odin is killed by Fenrir, who is in turn killed by Odin’s son, Víðar (Vidar). Thor and Jörmangand, the Midgard Serpent, kill each other. Surt kills Freyr before destroying Midgard with fire.

View this post on Instagram

However, after all this death and destruction, a new world rises up. Some Æsir survive Ragnarok, including Thor’s sons Magni and Móði (Modi), Odin’s sons Vidar and Vali, and Hoenir. Baldr and Höðr (Hod) also return from Hel and reunite with the others at Iðavöllr (Idavoll), a field in Asgard untouched by the battle. The human race also continues through two humans named Líf (Life) and Lífthrasir (Life Yearner).

In this way, Ragnarok is not just the end of the old, but the beginning of the new.

For an extensive guide to the Norse gods, myths and locations, I recommend John Lindow’s “Norse Mythology: A Guide to Gods, Heroes, Rituals, and Beliefs”, which was extremely useful when writing this article.

The sources of our Norse mythology knowledge

So, where does Norse mythology come from? Are these the stories that the Vikings told each other? The short answer is: we don’t know.

Before the Christianisation of the Nordic countries, the region was pagan, a term that here refers to a “a pre-Christian religion”. Unlike Christianity, Norse paganism was not an organised religion, and was instead personal to the individual. This might explain why we have little to no records of what Vikings believed or how they practised their beliefs.

We do have artefacts from the Viking era that appear to reference Norse mythology, such as the Eyrarland Statue, which is thought to depict Thor, or the “Valkyrien fra Hårby” figurine, which is thought to be a valkyrie. However, there is no accompanying explanation that confirms that these objects are or what they were used for. Written references to the gods and mythology on runestones are equally ambiguous.

Read more: Viking Runes: The Historic Writing Systems of Northern Europe

Our main sources for Norse mythology, and the sources we use to interpret any subsequent findings related to Norse mythology, are the sagas.

While the gods and myths do feature in other Icelandic sagas and poetry, the Eddas are considered to be the most important for our understanding of Norse mythology. However, despite providing answers, the term “edda” is a mystery in itself as no one knows what it actually means, with theories ranging from “poetry” to “great-grandmother” to a form of “kredda” (which means “superstition”).

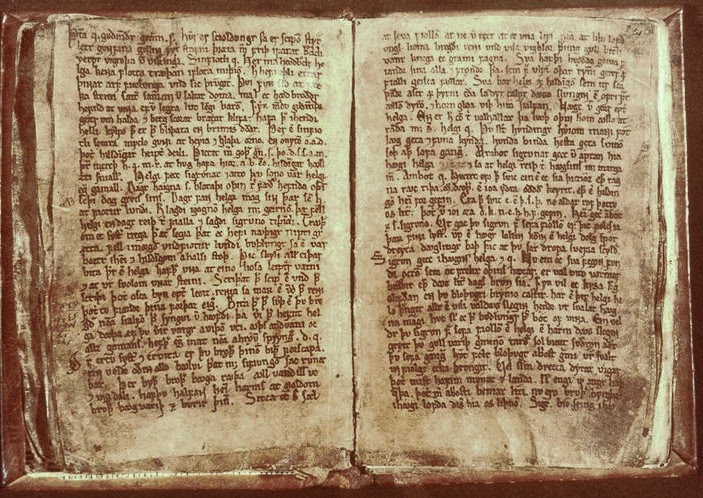

The Poetic Edda is a collection of mythological poems by unknown authors that mainly come from a manuscript known as the Codex Regius, which is Latin for “the King’s Book”. The Codex Regius is dated to around 1270 but was only discovered in 1643, when it came into the possession of an Icelandic bishop named Brynjólfur Sveinsson. Originally, these poems were thought to have been written by Sæmundr Sigfússon, but this is now thought to be unlikely. The Poetic Edda also contains poems from other manuscripts, such as “Baldrs draumar” (Baldr’s dreams), but it is usually up to the translator or editor to decide which poems they would like to include.

If you want to read the Poetic Edda for yourself, I recommend Carolyne Larrington’s translation.

The Prose Edda is often attributed to Icelandic writer Snorri Sturluson, and therefore also often referred to as the “Snorra Edda”. It is made up of four parts: the Prologue, Gylfaginning, Skáldskaparmál, and Háttatal.

Versions of this Edda can be be found in four manuscripts: the Codex Regius (14th century) – though this is not the same Codex Regius as the one that contains the Poetic Edda – the Codex Wormanius (14th century), the Codex Upsaliensis (14th century), and the Codex Trajectinus (17th century).

If you want to read the Prose Edda for yourself, I recommend either Jesse Byock’s translation or, for a challenge, Anthony Faulkes’ edition in Old Norse.

The Prose Edda is also known as the “Younger Edda”, as it cites poetry from an older source. When this poetry was found in the Poetic Edda, it was assumed that this was the poetry that Snorri had used, which is why the Poetic Edda is also known as the “Elder Edda”. However, this could not be the case, as the Prose Edda came thirty years after Snorri’s death in 1241. Instead, scholars now believe that both Eddas are based on the same, earlier poetry, though this has not yet been found.

Both Eddas were written around two hundred years after the Christianisation of the Nordic region. And speaking of the Christians…

What’s Christianity Got to Do with It?

The Christianisation of the Nordic countries was a long process and happened relatively late compared to the rest of Europe. It took even longer for pagan practices to die out completely, as many people were happy to adopt the Christian God in addition to the Norse ones, but weren’t as keen to adopt the Christian God instead of the Norse ones. Therefore, for a long time, the two religions coexisted in the same space – and often in the same people.

The Christian-Pagan dynamic is present in many sagas. In Chapter 98 of Njals saga, both Jesus and Thor are referenced as part of an argument between Thangbrandr, a Christian missionary, and Steinnun, a pagan preacher:

“Hast thou heard,” she said, “how Thor challenged Christ to single combat, and how he did not dare to fight with Thor?”

“I have heard tell,” says Thangbrandr, “that Thor was naught but dust and ashes, if God had not willed that he should live.”

As history shows, Christianity eventually won as the dominant religion of the Nordic countries. However, without Christianity we might not know about Norse mythology at all.

Pre-Christianisation, stories were passed on by hearing someone tell them rather than reading them in a book. It was the Christians who wrote the myths down, thereby preserving them for future generations.

On the other hand, this also means that we cannot know for sure how much of these myths as we know them have been impacted by Christian beliefs. Strange as it may seem, there are lots of similarities between Christian mythology and Norse mythology.

Read more: Viking Religion: From the Norse Gods to Christianity

For example, the character of Baldr, who is the son of Odin and loved by everyone but killed through no fault of his own and sent to Hel – only to return after the apocalypse to rule a new world… stop me if you’ve heard this one before.

A Christian influence can particularly be seen in the Prologue of the Prose Edda, as the author explicitly apologises for his ancestors’ pagan beliefs. According to this account, the Norse gods were great (but human) warriors who came from the East, specifically Turkey. They were so impressive that when they later travelled north to Scandinavia, people mistook them for gods and worshipped them.

Even poems in the Prose Edda that might come from the Viking era, such as Völuspá, may not have escaped a Christian influence, as Christianity was around at the time. Since the myths were passed from person to person, it is possible that there was never “one” correct version of the myths anyway but many different versions, as each storyteller added their own creative spin.

Therefore, it would have been very easy for Christian elements to be incorporated into the myths. It may even have been encouraged as a conversion technique, in order to make the transition smoother from paganism to Christianity by presenting the two religions as similar.

While scholars disagree on exactly where the different myths fall on a scale of “Completely Pagan” to “Completely Christian”, the majority agree that it is very unlikely that Christianity had no impact on the myths.

As John Lindow says: “If we are to accept that eddic poetry is a pagan myth, we must accept that two and a half centuries of Christianity wrought no changes in the eddic texts. This is of course possible, but it cannot be demonstrated” (2005:30).

Modern Day Impact of Norse Mythology

Even though Norse mythology is a web of stories and culture that we may never fully untangle, they are still truly fantastic stories that are loved by a multitude of different people.

Read more: 11 Viking Video Games to Play Before You Reach Valhalla

However, this love for the Norse myths can sometimes result in people becoming unnecessarily protective of preserving their “purity” – which is a task doomed from the start since, as shown above, we have no idea whether the Vikings knew the myths as we do.

It is through adaptation and reinvention that old myths survive, as a whole new generation of people are inspired by and fall in love with the stories.

This is especially true for Norse mythology, which owes its entire survival to adaptation – first by the storytellers who originally told these stories, then by the Christians who wrote them down, and now by the people creating TV shows, movies, books and video games inspired by the Norse gods and their adventures.

View this post on Instagram

What’s your favourite Norse myth? Do you have any questions about Norse mythology you would like us to answer? Let us know in the comments below!

Very good intro to norse mythology. When i went looking for sacred sites of norse mythology i came across this website.

I see there and in other places that people use norse and germanic both. Are they the same or is there difference?

Wow! Bloody confusing, but fascinating at the same time. Going to read it again to try and get my head around it all!

Just a lost American with no heritage trying to figure where my blood line came from . Appreciate the information and the the time.

I’m still very confused but not any fault to you just allot of information 🤔😊