In Norway, farmers in the mountains call their animals home by singing to them. Join us as we dive into the past, present and (potential) future of this curious tradition known as kulning.

If I asked you to name something that you might see in Norway, what would you answer? Maybe you would mention Viking ships, the fjords, the northern lights or even moose?

Whatever you said, “a woman standing in a field and singing in a high-pitched voice to some cows” probably wasn’t it. And yet, “kulning” (aka the practice of singing to your animals to get them to come home) has a long tradition in Norway, as well as Sweden and Finland.

Kulning comes from the farming tradition

Norway’s mountainous terrain and extreme weather conditions mean that farmers have to get creative with the resources they have.

Traditionally, farmers would move their animals to a mountain farm, known as a “seter”, in the spring, to allow them to graze freely throughout the summer.

They would then move the animals back off the mountain in the autumn, where they would either be temporarily housed in a big barn for the winter – or more permanently housed in the Big Farmyard in the Sky via the abattoir.

This journey to and from the mountain was known as “bufaring” – and everything I’ve read about it suggests that trying to herd a load of farm animals along narrow country roads was not an easy or quick task (apparently sheep are the worst).

Once you had successfully managed to get up the mountain with all your animals (and your sanity) intact, you then had to not lose any animals while you were up there.

If the idea of spending your summer running around the mountains after mischievous cows or stupid sheep doesn’t sound appealing to you – it didn’t sound appealing to Norwegian shepherds either. A solution had to be found – and that solution was kulning.

“It is a common belief that animals can recognise and distinguish between certain tones and alluring sounds,” wrote Norwegian Folklorist Ådel Gjøstein Blom in his book, Folkeviser i arbeidslivet (“Folk songs in working life”). “Therefore, it is likely that certain song traditions have become attached to different phases of working with animals.”

Kulning is a woman’s job

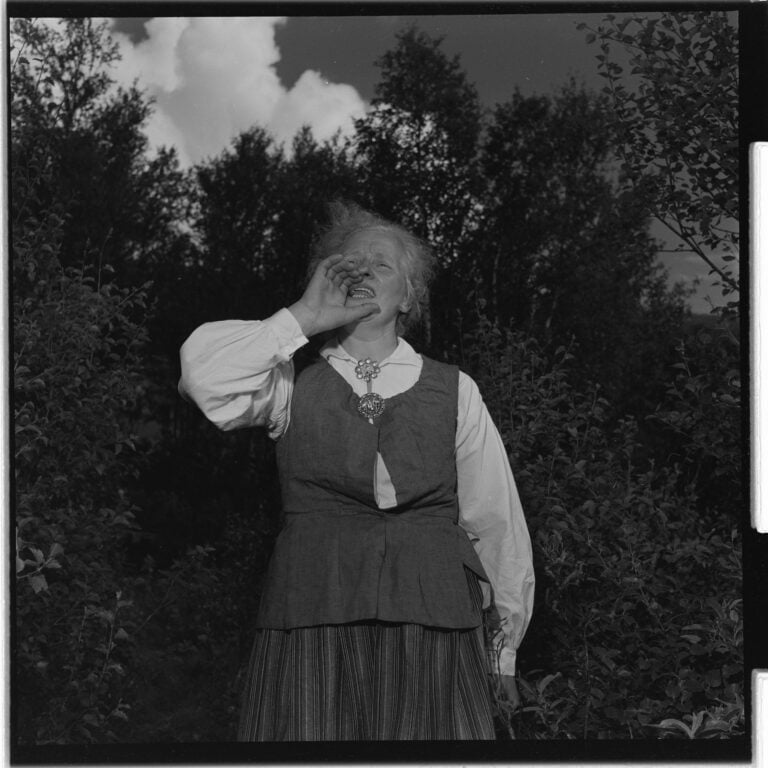

Norwegian shepherds were traditionally women, and therefore, the vast majority of kulning singers were (and continue to be) women.

Part-singing, part-shouting, the women could stand at the edge of the field and call out in high-pitched tones. The sound would carry through the mountains and valleys, ensuring that the animals would hear it, no matter where they had got to, and know that they needed to return to the farm.

As with other folk practices, such as rosemaling, kulning was a skill learnt from life and other people rather than formal training. As such, there was no “uniform” way of kulning, and each singer would develop their own style, which their animals could recognise.

Different types of kulning for different animals

That said, there were different types of kulning for different types of animals. These are known as “lokk”, which comes from the verb “å lokke”, meaning “to lure” or “to coax” (“lokking” is another word for kulning).

The most melodically complex was the “kulokk”, which was used to summon cows. “Geitelokk” and “sauelokk” were much more simple, often a single note or a shout, proving beyond a shadow of a doubt that goats and (especially) sheep are the idiots of the farm world.

But if kulning can call animals, then surely it can be used to call people too?

Kulning is not used for people

When I was a child, my very Northern English dad was very successfully able to call me,and my siblings over with a single, very loud “OI!”.

Could that be considered kulning? Does that then prove that children are the sheep of the human world in terms of intelligence? Well – not quite.

Kulning is used solely for human-to-animal communication. “Laling” or “hugning” is human-to-human communication.

Much like kulning, laling is a type of shout-song that developed for practical reasons on the seter to send a message to another person, whether that be a shepard out with the animals or someone on a neighbouring farmstead. In this respect, laling is similar to the Swiss practice of yodelling.

However, in folklore, people could still be susceptible to kulning – as long as it wasn’t another person who was singing.

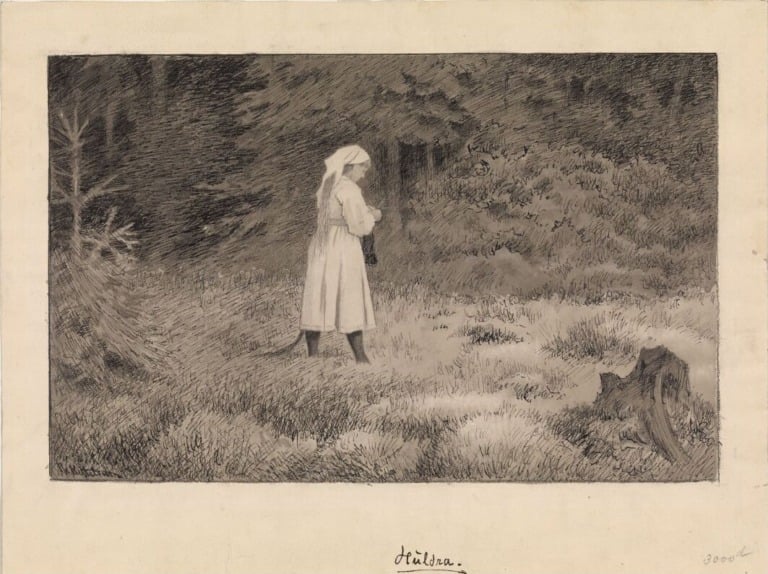

The hulder is a Norwegian troll who looks like a beautiful woman – except for her long cow’s tail. According to folklore, the hulder often visits seter, trying to find a young man to seduce.

Given the imagery of young women on seter calling for their animals, it’s unsurprising that stories of the hulder are closely connected to the kulning tradition.

If the “kulokk” is to lure cows, and the “sauelokk” is to lure sheep, the “huldrelokk” is to lure a different type of animal all together: men.

Kulning is not joiking

If you only remember one thing about kulning from this article, let it be this: kulning is not joiking.

Joiking is a type of traditional singing practiced by the Saami – the indigenous people of the Nordic region. Unlike kulning or laling, which were born out of practicality, joiking is a way of passing on stories and ideas. Joiks can be personal or spiritual, and can play a role in shamanic practices.

As with other aspects of Saami culture, joiking went through a period of being heavily repressed by the Norwegian State. It is thought that its connection with shamanism drew particular ire, as it was considered to be anti-Christian and even “devilish” music.

Thankfully, joiking did not die out, and Saami singers like Mari Boine have played a big role in its revival. In 2019, the Norwegian-Saami band KEiiNO featured joiking as part of their Eurovision entry song “Spirit in the Sky”, which won the popular vote.

Kulning in Frozen

So, what do you do if you want to hear some kulning but aren’t able to travel to Norway? Well, if you have a child under the age of 10 (or you just don’t live under a rock), you’ve probably already heard it without realising it.

The Disney movie Frozen features kulning throughout its soundtrack, particularly whenever Elsa uses her powers. The kulning was sung by Norwegian-Swedish singer Christine Hals, who grew up using kulning to herd goats.

Kulning also inspired the siren call that was used throughout Frozen 2, this time sung by Norwegian singer, Aurora.

The future of kulning

While kulning is still practised on seter in Norway, Sweden and Finland today, the farms themselves are becoming less and less common. According to the Norwegian statistics bureau, the number of seter in active operation in Norway almost halved between 2005 to 2020, going from 1,403 to just 781.

However, kulning is no longer confined to the mountains, it is now recognised as a professional singing style. If you’re interested in listening to kulning, you’re much more likely to hear it now in a concert than in the mountains.

This is a double-edged sword, as while kulning’s survival is no longer tied to the seter, it has almost become too removed from its roots, to the point that some farmers do not feel like they can describe what they do as kulning anymore.

Personally, I feel a little torn about this. I’m by no means a proponent of “tradition for traditions’ sake above all else”, and I think a thing’s ability to adapt is what ensures its survival. Similarly, I don’t doubt the sincerity or skills of the professional kulning singers.

All the same, I hope that kulning doesn’t become so elite that it is taken away completely from the people that it originated from. If something’s worth preserving, then surely it’s also worth sharing. Kulning belongs on farmsteads just as much as in concert halls.

However, if you do see a woman kulning in the mountains, maybe check to see if she has a cow’s tail – just to be safe.

What do you think about kulning? Would you ever try to use kulning to get your cat to come in from the garden? Did it work, or did it just stare at you disdainfully while you embarrassed yourself in front of your entire neighbourhood? Let us know in the comments!

Sheep and goats the “idiots of the farm”?; this only goes to show how little people in general know about the intelligence of such animals.