The stunning Norse-inspired St. Olaf's church in Balestrand is a charming stop on a tour of Norway's Sognefjord region. Here is its fascinating story.

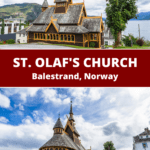

At first glance, St. Olaf’s Church in Balestrand looks like it belongs to the Middle Ages. It is all timber and turrets, with carved dragon heads that feel lifted from Viking lore.

Step closer, though, and the picture shifts. The church is Anglican rather than Lutheran, it is just over a century old rather than medieval, and it was built as an act of love and remembrance by a Norwegian hotelier for his English wife.

Few places on the Sognefjord tell a more human story than this little wooden church with a big heart.

The Setting: Balestrand on the Sognefjord

Beautiful Balestrand sits on the northern shore of Norway’s longest and deepest fjord, a village framed by calm water and steep mountains that glow pink on summer evenings. The location drew nineteenth-century travellers long before mass tourism existed.

Artists came for the light, climbers came for the peaks, and British visitors in particular made Balestrand a seasonal home. Elegant Kviknes Hotel grew with this traffic, becoming the grand waterside hub that it remains today.

The combination of fjord scenery, fresh mountain air and genteel hotel life gave Balestrand an international flavour unusual for a small Norwegian community.

A Love Story with Deep Roots

Among those Victorian visitors was Margaret Sophia Green, daughter of an English clergyman and an avid mountaineer. She fell for both the landscape and a local, marrying hotelier Knut Kvikne in 1890. But tragedy quickly followed.

Margaret developed tuberculosis and died in 1894, only four years after her wedding. Before she passed, she told her husband she longed for an English church in Balestrand, a place where the many foreign guests could worship in a tradition familiar to them.

Knut honoured that wish. He set aside a plot near the hotel and pushed the project forward with local support. Three years after her death, the church was complete.

It was dedicated to St. Olaf, Norway’s patron saint, an apt bridge between British visitors and Norwegian heritage.

Who Built It and When

The church we see today dates to 1897. Knut engaged the young Norwegian architect Jens Zetlitz Monrad Kielland, who would later become known for significant buildings in western Norway.

Among others, the designed Bergen railway station and several other notable buildings in Norway's second city.

Kielland designed St. Olaf’s as a stave-style imitation in the then-fashionable dragestil, a national romantic style that revived medieval forms and motifs in contemporary wood architecture.

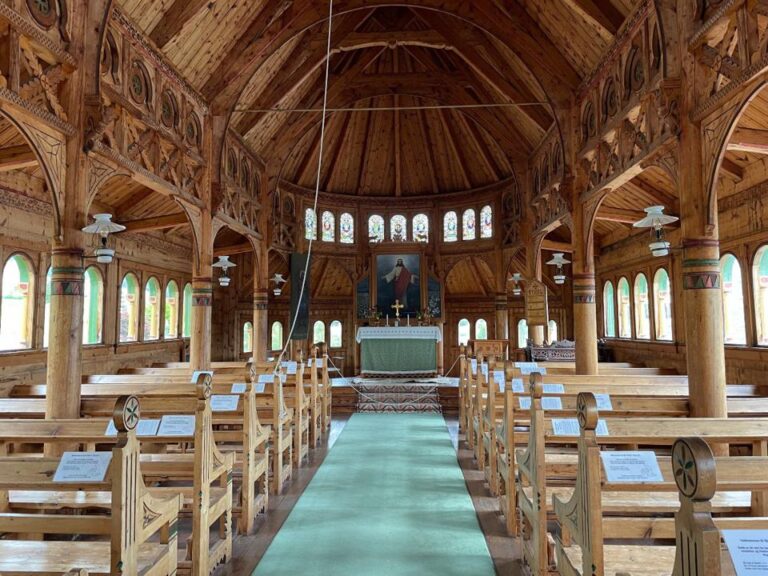

Local craftsmen brought the drawings to life with traditional carpentry. The result is a small, beautifully proportioned long church in timber that seats just under a hundred people. The figure usually given is ninety-five.

A Norwegian Exterior with English Purpose

From outside, St. Olaf’s reads as Norwegian through and through. There are two slender spires, a ridge turret on the nave, and dragon heads at the roofline, details that echo the expressive carvings of Norway’s medieval stave churches.

The wall cladding and profile belong to the same family of forms that travellers seek out at places like Hopperstad in Vik across the fjord, which makes the discovery of its Anglican identity all the more striking.

The blend is intentional. This is a church built to serve English-speaking worshippers, yet it wears a Norwegian architectural language that roots it in place.

Inside the Church: What To Notice

The interior is intimate and warmly lit, with exposed timber everywhere you look. Just inside the entrance hangs a painted portrait of Margaret along with a brass memorial plate.

The inscription reads, “The mountains shall bring peace,” a line from Psalm 72 that resonates with her love of climbing and the surrounding landscape.

It is a small detail that stops many visitors in their tracks, a quiet statement that this building is a memorial as well as a house of prayer.

The altar painting dates from 1897 and shows the Risen Christ, and a banner depicting St. Olaf is also believed to be original to that year.

In the choir, a suite of stained-glass windows features a thoughtful mix of saints: Norway’s Olaf, Hallvard and Sunniva, together with Mary, Columba, Clement, Bride, Swithun and George, a nod to the church’s English ties and wider Christian tradition.

The Anglican Connection in Norway

Although St. Olaf’s looks like a stave church, it belongs to the Church of England and forms part of the Diocese in Europe, historically overseen by the Bishop of Gibraltar.

In practical terms, that means the church offers English-language worship during the summer season, typically under a chaplaincy arrangement that works closely with the Church of Norway. It is a gentle, ecumenical presence in a village long accustomed to international visitors.

How the Church Survived and Still Serves

The church has always relied on community goodwill. Visitor donations keep the lights on and the timber maintained. Local hospitality is woven into its story.

Visiting clergy are traditionally hosted by Kviknes Hotel, a practice that dates back to the church’s consecration and underlines how closely the building is tied to Balestrand life.

Over the years, St. Olaf’s has become a sought-after wedding venue, especially for couples with British and Norwegian ties. It remains unlocked and welcoming when services are not underway, and even a short visit rewards the detour.

A Small Church with a Large Cultural Footprint

St. Olaf’s reached a global audience in an unexpected way. The church is widely cited as the inspiration for the chapel seen during Elsa’s coronation in Disney’s Frozen.

Whether visitors first learn about it through the film or through travel research, many arrive with a sense of déjà vu when they see the steep roofs, the crisp timberwork and the fjord beyond. The connection brings more people through the doors, which in turn helps secure the church’s future.

Planning Your Visit

Balestrand is easy to weave into a Sognefjord itinerary. Drivers approaching from the south can cross by ferry at Vangsnes, which lands close to the village. The church stands a short walk from Kviknes Hotel and the waterfront promenade.

In summer, services in English are advertised locally, and the door is usually open for quiet visits the rest of the day. Donations are appreciated and help with upkeep.

If you have time, pair your stop with a side trip across the fjord to Hopperstad Stave Church in Vik. Seeing the medieval original and this late-nineteenth-century homage on the same day gives a satisfying sense of continuity in Norwegian woodcraft.

A Few Practical Notes

The church’s official English name is St. Olaf’s Church, but locals often call it Den engelske kyrkja (“the English Church”). The address commonly appears as Kong Beles veg in Balestrand, a short stroll from the ferry quay and the hotel.

Capacity is just under one hundred, so services feel intimate. Visitors should keep voices low, avoid flash photography during services, and consider a small donation at the door to support maintenance.

If you are planning a wedding or seeking service times, the Church of England’s Diocese in Europe pages and local tourist information are the best starting points