An introduction to fjernvarme, or district heating in Norway. What is it, how does it work, and why does so much of Norway have it?

As temperatures plunge across Norway, thoughts as always turn to heating. Foreigners considering moving here often email to ask us what to expect in terms of heating, energy bills and so on.

Heating your Norwegian home in cold weather can be done in a multitude of ways. Electric heating, heat pumps and wood-burning stoves all have their benefits and drawbacks.

One of the cheapest and most sustainable ways to heat your home in Norway is district heating, called fjernvarme (literally: remote heat) in Norwegian. This system is well-liked in Norway for many reasons.

So join us as we explore the ins and outs of district heating, its history, benefits and drawbacks, and the many reasons why it’s so popular in Norway. If you're about to move into a home with district heating, this is the post for you.

What is district heating?

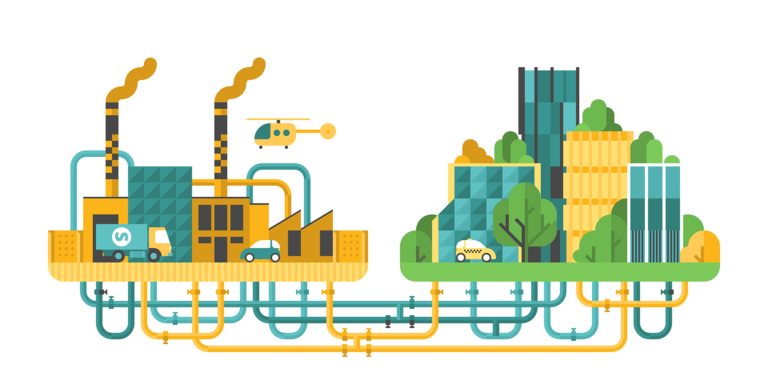

District heating refers to a system where heat is produced centrally and distributed to buildings via a network of pipes. The heat is usually transported in the form of hot water, but steam is another possibility.

Building the network of pipes necessary for the system to work is costly, so the investment is only worth it in areas that are densely built up. For this reason, district heating is usually found in Norway’s larger cities, and virtually absent in rural areas.

The ancient origins of district heating

District heating has its origins in ancient Rome, where the Romans used a system of central heating known as the hypocaust. The hypocaust consisted of a network of underground tunnels, over which hot air was circulated using a series of furnaces.

This hot air would then be directed into the floors and walls of buildings, heating them from the inside out. The Romans also used a similar system to heat public baths and other public buildings.

This early form of district heating was a highly advanced technology for its time, and it allowed the Romans to enjoy a level of comfort and luxury that was unmatched in the ancient world.

How district heating works

If you move into an apartment heated with district heating, you can expect a few things. First, radiators will be installed here and there around the house, typically close to windows.

Read more: Paying for Power in Norway

These radiators will be connected to pipes, which themselves are connected to a main hot water pipe coming in the apartment. The hot water flows in through the pipes, and to the radiators, where it releases its heat and heats up the room.

On the radiator itself is a tap-like knob that functions like a thermostat, allowing you to regulate the flow of water. In addition to the thermostat, the amount of heating provided by district heating is also regulated according to outside temperatures.

This means that if the outside temperature is very cold, the inflow will be warmer. In addition to the valves installed on the radiators themselves, some apartments have a main valve regulating the inflow of hot water into the house.

This valve is generally located in a utility room, together with the meter calculating how much heat has been used. Some buildings have only one such entry point for the whole building, and in those cases the total heating bill will generally be split between tenants according to apartment size.

You will receive a regular bill for the amount of hot water used. In these times of high electricity prices, those with district heating tend to see lower overall costs for energy than equivalent households not connected to a distrcit heating system.

The benefits of district heating

Heating your home with district heating has many advantages. The first is the quality of the heat itself.

Where electric heaters or wood burning stoves work in an on-and-off kind of way, providing their heat in bursts or waves, district heating provides a stable, continuous source of heat.

Another benefit is that the system producing the heat is located outside your house. This means that unlike a furnace, a heat pump or a fireplace, it requires no maintenance on your part.

From the city's point of view, producing heat centrally and distributing it to buildings has many advantages. The first one is an economy of scale.

Instead of having to build and maintain several different boilers to heat a city’s hospital, schools and office buildings, the city only builds one. This is less costly, and saves spaces in each individual building, since furnaces and boilers won't need to be fitted.

Another benefit is that the people operating the thermal energy plant are highly qualified and are focused on just that one task. For a smaller boiler or furnace dedicated to just one building, the person in charge will usually have the responsibility for many other systems, and is likely not to be a specialist in operating heating systems.

District heating and sustainability

This is a big one. When making improvements to the thermal plant supplying heat to the district heating system, you are making all the buildings that are connected to it more sustainable.

Take wood burning stoves, as an example. A homeowner using wood for heating may decide to install a more efficient and less polluting stove, which will make her house a bit more sustainable.

But that improvement will come at a significant cost to the homeowner, and will only affect their one house. An improvement at a district heating facility means that the heating of multiple homes and businesses will now be more sustainable, with the investment only having to be done once.

Many of Norway’s district heating facilities are connected to waste incineration plants, which solves two problems in one go – waste disposal and heat generation. In Oslo, a pilot project is in the works to equip the local incineration plant with a CO2 capture unit, which will make district heating in that area even more sustainable.

In Trondheim, the sewage processing plant is connected to the district heating network. This is because a by-product of sewage treatment is methane gas, which gets collected and burned to heat water that circulates in the district heating network.

Existing district heating grids also provide an opportunity for ensuring excess industrial heat does not go to waste. The data centres powering the internet, for example, use enormous amounts of electricity and generate a lot of heat.

Connecting these data centre’s cooling systems to existing district heating networks presents an interesting possibility to make good use of that heat energy. In essence, a district heating system provides a natural outlet for any incidental energy that in and of itself would not warrant the building of expensive infrastructure.

District heating networks in Norway

In 2021, district heating facilities delivered heat equivalent to 6,672 GWh to homes, industry and businesses. That’s more than the total electric consumption of Alaska for the same year.

Statistics show that district heating is growing in Norway. The amount of energy delivered has been roughly doubling every ten years.

More than half of the heat goes to businesses and public buildings such as schools, hospitals and municipal office buildings. About a quarter goes to private homes, while the rest goes to industrial facilities.

In some areas where district heating is available, regulatory authorities can force a property developer to connect a new building to the network. Exceptions can be made if the building is equipped with an even more sustainable source of heat (a combination of passive heating and solar panels, for example).

Regulation may force the hand of developers in some cases, but common sense is usually sufficient, since having a property connected to district heating is a good sales argument.

District heating and the energy crisis

District heating has shielded many Norwegian consumers from the effects of the energy crisis. Prices have gone up, but not nearly as much as the electricity prices.

That being said, government support programmes for electricity bills, which do not apply to district heating, may end up equalising much of the difference.

Tell us what you think

Do you have any experience with district heating? What do you think about the idea of heating your house with an outside source of heat? Let us know in the comments!

Very well explained article for district heating !.