In a country with so many mountains and so much winter snow, avalanches are a genuine risk in much of Norway. Here's what you need to know, whether you're a resident or visitor.

I first published this article in 2022. At the time, it felt important. Now, it feels personal.

Just a few weeks ago, a good friend of mine died in an avalanche high in the mountains of Hemsedal. He was just 40.

He was a deeply experienced outdoorsman, someone who embraced friluftsliv—Norway’s outdoor life philosophy—in everything he did. Nature was his passion. The news of his death came as a bolt from the blue.

Avalanches can feel like something that only happens to other people, or to those who are careless. But that’s not the reality. My friend knew the mountains inside out, and yet he still lost his life.

Avalanche risk is real, and it doesn’t matter how experienced or careful you are—it’s a threat we must all respect.

That’s why I’ve chosen to revise and republish this article. Whether you’re a local or a visitor, it’s vital to understand the risks and take the right precautions when heading into Norway’s stunning, snowy wilderness.

Avalanche Season in Norway

At this time of year (late March), barely a day goes by without a report of another avalanche somewhere in Norway. People die every year in the mountains of Norway, both locals and tourists.

It’s a sad reality, and unfortunately not a surprising one: around 7% of Norway is considered at risk of avalanches.

If you live in or are visiting a mountainous region—perhaps for skiing or hiking—there are some essential things you should know to stay safe.

What is an Avalanche?

Most people have a general idea, but it’s worth taking a closer look.

An avalanche is a rapid flow of snow down a slope—typically a mountainside—caused when the layers of snow become unstable and collapse under their own weight or due to an external trigger.

Avalanches can vary widely in size and speed. Some are small and relatively harmless, while others can thunder down a slope at speeds of over 100 km/h, carrying tonnes of snow, ice, rocks and debris with them. In many cases, there’s no time to react once one is triggered.

These events are usually caused by a combination of factors. Weather plays a big role—heavy snowfall, sudden temperature changes, rain falling on snow, or strong winds moving snow around and creating unstable layers.

Human activity is another common trigger. Skiers, snowboarders, snowmobilers and even hikers can disturb a fragile snowpack and set off an avalanche. In rare cases, natural causes like earthquakes or wildlife movement can also be responsible.

Avalanches are most likely to occur on slopes between 30 and 45 degrees in steepness. Slopes that are too flat don’t allow the snow to build up enough momentum, and slopes that are too steep often slough off snow before large accumulations form.

During winter in Norway, avalanches are not just a backcountry concern. They regularly close mountain roads and railway lines, affecting everything from weekend ski trips to everyday commutes.

Key transport routes, such as the E39 or the Bergen and Rauma railway lines, are sometimes shut down due to avalanche danger.

In especially hazardous conditions, entire communities may be cut off or evacuated—not because an avalanche has occurred, but because the risk alone is enough to warrant it.

Avalanche Forecasts in Norway

Detailed avalanche forecasting is available from the Norwegian Water Resources and Energy Directorate (NVE), together with warnings for floods and landslides. The service has been in place since 2013.

Serious avalanche risk is usually also highlighted in weather forecasting apps.

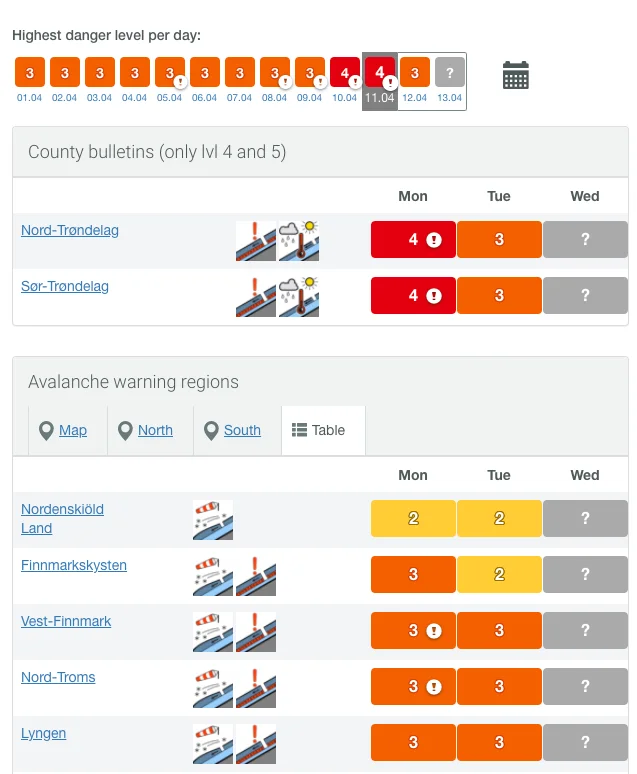

The website varsom.no gives the danger level for various regions and mountain ranges based on international standards. I took the example screenshot below when writing this story:

Danger level 1 – low: The snowpack is well bonded and stable in general. Triggering is generally possible only from high additional loads in isolated areas of very steep, extreme terrain. Only sluffs and small-sized natural avalanches are possible.

Danger level 2 – moderate: The snowpack is only moderately well bonded on some steep slopes, otherwise well bonded in general. Triggering is possible primarily from high additional loads, particularly on the indicated steep slopes. Very large-sized natural avalanches are unlikely.

Danger level 3 – considerable: The snowpack is poorly bonded on many steep slopes. Triggering is possible, even from low additional loads, particularly on the indicated steep slopes. In some cases large-sized, in isolated cases very large-sized natural avalanches are possible.

Danger level 4 – high: The snowpack is poorly bonded on most steep slopes. Triggering is likely even from low additional loads on many steep slopes. In some cases, numerous large-sized and often very large-sized natural avalanches can be expected.

How to Reduce Your Avalanche Risk

First and foremost, pay attention to the avalanche forecast and choose your routes appropriately. You can also consider avoiding classified avalanche terrain regardless of the forecast. These are available for the regions Romsdalen, Lofoten and Troms.

When you go, make sure you are fully prepared with the proper gear including avalanche safety equipment. Knowing how to navigate safely and survive during harsh, cold conditions are important skills for your group to have.

If you are familiar with skiing elsewhere, be wary of overconfidence. Ski touring conditions in Norway can be quite different. Mainly, the sun plays a much more important role later in the season than elsewhere. Also, long periods with persistent weak layers are common, particularly away from the coastline.

Types of Avalanche in Norway

Avalanches are typically related to one of more of the following conditions: new snow, wind-drifted snow, a persistent weak snow layer, wet snow, or gliding slow. Different conditions can cause loose-snow avalanches and slab avalanches.

Loose-snow avalanches typically related to recent snowfall, releasing unbound loose snow. They start at a point and get wider on their way down.

Slab avalanches are quite different. Once triggered, an entire section of snow–typically bonded slow lying on top of a weak layer– falls. They have a distinct, broad fracture line.

You can read more about the types of avalanches in Norway here.

Living in Avalanche Prone Areas

In recent decades knowledge about avalanche risk has increased greatly. If you live in a mountainous area of Norway, there's now plenty of information you should know.

In high-risk areas, measures have been put in place to protect buildings. These include walls and fences. For example, NGI oversaw the construction of a 360-metre-long embankment wall above a hotel in Loen in 2015.

The town of Longyearbyen on Svalbard has been one of the most avalanche prone areas of Norway in recent years. Our changing climate has seen more winter rainfall, causing several serious avalanches that claimed lives. People living in several parts of the town have since been permanently relocated.

Fences on steep mountainsides in urban areas are a common sight in Northern Norway. The picture below shows the fences installed in Hammerfest.

Extensive research has fed into the Planning and Building Law. New private homes are not permitted to be built in areas in which the avalanche probability per year is. greater than 1 in 1,000.

The requirement for the construction of hotels, hospitals, kindergartens, etc. is 1 in 5,000. The same rules apply for landslide risk.

Avalanche Research in Norway

The Norwegian Geotechnical Institute (NGI) is an independent international centre for applied research and consultancy in engineering-related geosciences, integrating geotechnical, geological and geophysical expertise. They serve as Norway's competence centre for avalanches.

“Our core expertise is related to the mechanisms and the conditions that lead to avalanches, as well as relevant protection against avalanches and measures that can reduce the risk associated with avalanches,” states the NGI website.

The challenges and NGI research efforts relating to avalanches include:

- modelling and calculation of run-out distance and forces

- full-scale measurement of avalanches at Ryggfonn

- methods for surveying avalanche-prone areas

- new avalanche warning methods and emergency routines

- protective measures against avalanches, such as catching dams and snow fences.

NGI engages in international projects with expertise from France, Switzerland, Austria, Italy, the USA and Japan.

A Final Word

Avalanches are part of life in a country with mountains as majestic and snow-filled as Norway’s. But they are also deadly and unpredictable.

Whether you’re hiking, skiing, snowmobiling or simply admiring the view, take the risks seriously. Check the forecast. Learn the terrain. Carry the gear. And above all, never assume that experience alone will keep you safe.

I wish I didn’t have a personal story to tell. But now I do. Stay safe out there.