Both the Norwegian Roald Amundsen and Brit Robert Falcon Scott led expeditions to the South Pole within weeks of each other. Unfortunately, things didn't work out for one team on the return leg.

In these times of travel restrictions, I've been reading a lot more. Right now, I'm deep into an old book by one of my favourite authors, Kim Stanley Robinson. Published in 1997, Antarctica follows characters living at and visiting research stations in Antarctica.

In the book, there are many references to the expeditions of Scott and Amundsen, who battled to be first to reach the South Pole in the southern summer of 1911-12.

Table of Contents

The world's greatest expeditions

Between December and January, the two teams reached the Pole within five weeks of each other. Sadly, Scott and his team all died on the return journey, while Amundsen's team all returned to their basecamp at Framheim.

Read more: Norwegian Polar Explorers

It's made me realise how much I heard about Scott at school and popular culture back in the UK. Whereas here in Norway, all I ever hear about is Amundsen!

Having heard the stories over and over again from both perspectives, I thought it was time to write about it. Grab something warm to drink and enjoy!

Antarctica and the South Pole

Antarctica is the world’s southernmost, highest, driest, windiest, coldest and iciest continent. Most people are aware the landmass is almost totally covered in ice, but sometimes it's hard to appreciate its sheer size. The continent's size is about 14.2 million square kilometres (5.5 million square miles).

Despite its perception by some as a vast sheet of ice, Antarctica's landscape varies considerably. East Antarctica is mostly a very high, ice-covered plateau. In contract, West Antarctica is mostly an archipelago of mountainous islands covered in ice.

Read more: Norway and Antarctica

These two distinct regions are separated by the Transantarctic Mountains, a range of approximately 3,400 kilometres (2,100 miles) in length. The continent is home to approximately 90% of the world’s ice and 80% of its fresh water. While there are no permanent settlements, several research stations are manned year-round.

The South Pole is actually two different places. The Geographic South Pole marks the Earth's southernmost axis of rotation. This is distinct from the Magnetic South Pole, the position of which moves and is defined by Earth's magnetic field. That being said, it's the first of these that we usually take to mean the South Pole.

The point sits on top of a barren, icy plateau at an altitude of 2,835 metres (9,301 ft) above sea level. At this point, the ice has an estimated thickness of 2.7km. If accurate, that would make the land underneath the South Pole to be not that much higher than sea level.

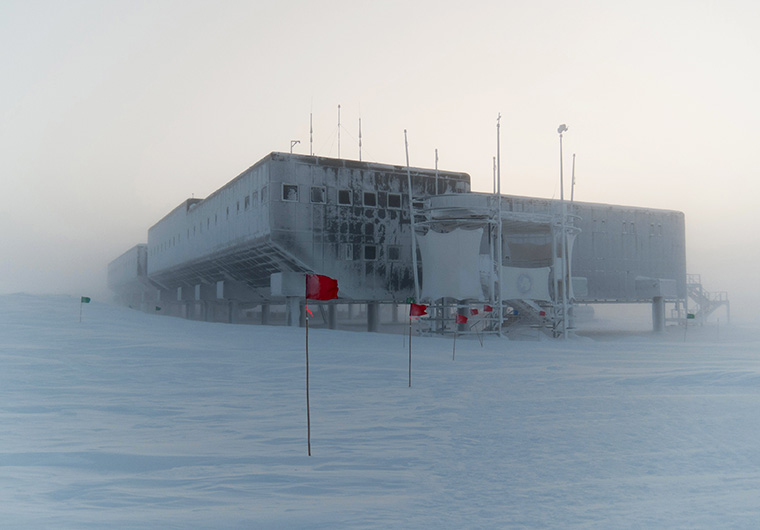

The United States administers a research station close to the South Pole, named after the two explorers. It is home to a year-round population of around 50 scientists and support staff. That number rises to around 200 in the summer season.

It is the only inhabited place on Earth from which the Sun is continuously visible for six months and then hidden for six months. During that period of darkness, air temperature can drop as low as -73°C (-99°F) while the station is hit by blizzards and gale-force winds.

Who were Amundsen and Scott?

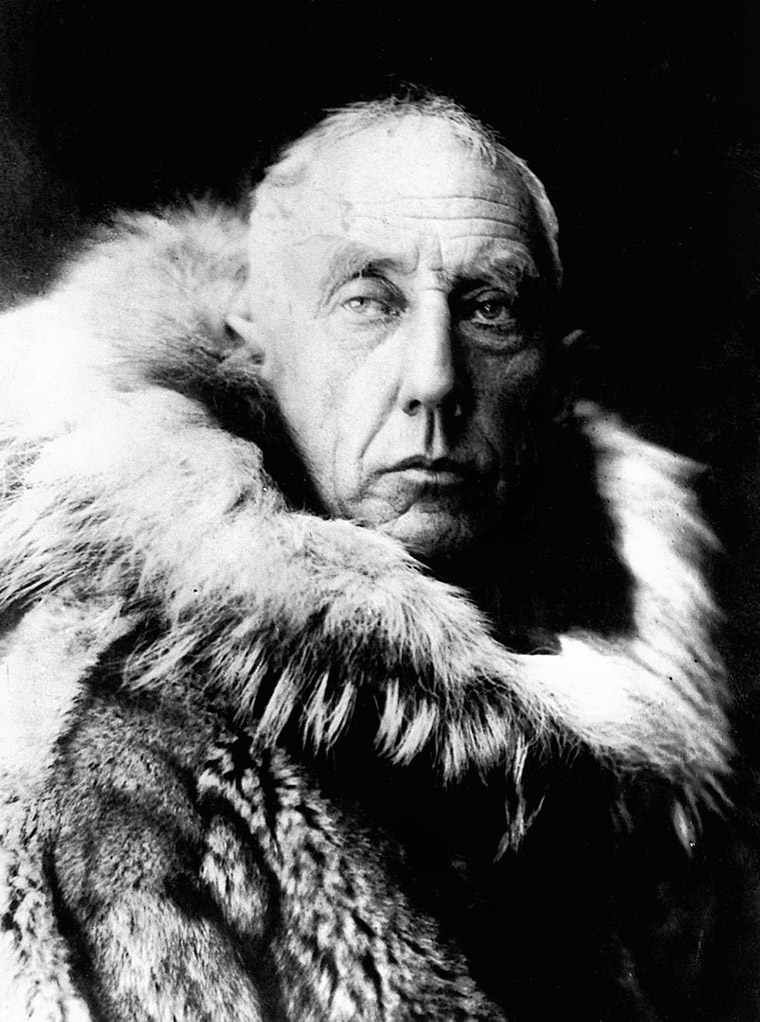

As this is a blog about Norway, let's start with the Norwegian. Roald Amundsen was fascinated by polar exploration from an early age. He quit his university studies to head out to sea with Arctic whalers, before joining the Belgian ship Belgica, which in 1899 was the first expedition to winter in the Antarctic.

From 1903-06, Amundsen sailed through the North-West Passage in his own ship Gjøa, another first. He then planned to trek to the North Pole, but turned his attention south when he heard Americans had beaten him to it. His desire to claim the South Pole for Norway drove him for several years.

Read more: Famous Norwegians

The UK's Captain Robert Falcon Scott also had his eye on seafaring from a young age. He joined his first ship at the young age of 13, going on to become a Royal Navy officer.

Scott’s Antarctic ordeal began over a year prior to the attempt on the Pole. His vessel Terra Nova arrived on Ross Island with a team of 34. Although his team were there to conduct scientific research and collect wildlife and rock samples, he had set his sights on the South Pole.

Setting course for the South Pole

Before leaving on the research expedition, Scott had vowed “to reach the South Pole and to secure for the British Empire the honor of this achievement.” However, Amundsen had a similar desire.

The Norwegian chose to change course to Antarctica once he had heard that Americans had conquered the North Pole. According to historical records, he didn't tell his financial backers or even many of his crew aboard the Fram until they were well on their way.

Before arriving at Antarctica, Amundsen sent a letter to Scott—who was preparing his expedition in Australia—to signal the start of the race. It is said to have simply read: “Beg leave to inform you Fram proceeding Antarctic. Amundsen.”

Read more: The History of Norway

The two expeditions took very different routes to the Pole. Amundsen chose the Ross Ice Shelf in the Bay of Whales to set up his camp Framheim. Scott's base in McMurdo Sound was good for the scientific research but sixty miles further away from the South Pole than Amundsen's camp.

The race wouldn't begin immediately, however, as preparations had to be made. This included laying down caches of food and other supplies along the proposed route. Both parties also took shelter for several months waiting for the winter to finish and the sun to return.

The race to the South Pole begins

Amundsen made an attempt to start early in September 1911, but was forced to return as they experienced extreme low temperatures. They tried again, successfully, on 20 October. Scott's team got going a few days later on 1 November. Given the earlier start and shorter distance, Amundsen was off to a flier.

The preferred transport was a major difference between the two parties. Scott used sled dogs, ponies, and even some motorised tractors. However, the machines quickly broke down and the Manchurian ponies were too weak to cope with the cold and had to be killed. Scott's team was forced to spend much of the trek hauling their sledges on foot.

In contrast, Amundsen's team relied on skis and sled dogs. The dogs helped the team save strength. The team killed the weakest dogs to supplement their supplies. They also helped Amundsen's team move at around 20 miles per day, much faster than Scott's.

However, the Norwegians took an untested route that included a frozen maze of dangerous crevasses, mountains and glaciers. While their final route was far from optimal, they still made good progress.

On December 14, 1911, Amundsen's team planted the Norwegian flag at the South Pole. They stayed to rest for just a couple of days before setting out on the return journey.

The diaries of the polar explorers

Much of what we know about the two expeditions comes from diary entries. Amundsen wrote of his excitement as they neared the goal, saying he “had the same feeling that I can remember as a little boy on the night before Christmas Eve—an intense expectation of what was going to happen.”

A few days before arriving, without knowing they had already lost the race, Scott wrote: “Another hard grind in the afternoon and five miles added. Our chance still holds good if we can put the work in, but it’s a terribly trying time.”

Upon reaching the Pole, Scott's team spotted the remnants of Amundsen's camp: “Great God!” Scott wrote in his diary. “This is an awful place and terrible enough for us to have labored to it without the reward of priority.”

The tragic end of Scott and his team

The extended time taken by Scott's team to reach the Pole caused several problems for their return. It was already late into the summer, meaning temperatures were dropping quickly. They were also short on supplies, and suffered from exhaustion, frostbite and malnourishment.

Around 20 days after Amundsen's group had made it back to their base camp, the first of Scott's team died. One month later, another frostbitten team member apparently sacrificed himself to avoid slowing down the team. According to diary entries, he said “I am just going outside and may be some time.” He did not return.

The three remaining men continued their journey but were caught in blizzard forcing them to stop. They died in a tent just 11 miles from a supply cache. By the time their bodies were found many months later, Amundsen was back in Norway on a lecture tour.

Scott's last diary entry read: “We shall stick it out to the end, but we are getting weaker, of course, and the end cannot be far,” Scott wrote in his last diary entry. “It seems a pity, but I do not think I can write more.”

The legacy of Amundsen and Scott

Such was the achievement of Amundsen, it would be more than 40 years until another human set foot on the South Pole.

Both men have left a major legacy for exploration and on Antarctica itself. The Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station is a USA-operated scientific research station at the South Pole.

Scott has gone down in history for his heroic failure, especially in his native England. Speaking from a visit to Antarctica, Scott's grandson told BBC News that his scientific legacy should be better appreciated.

“It was a very significant part of the expedition. They undertook the science in very extreme conditions with amazing endurance. You only realise that when you come down here. There was no contact with the outside world and the risks were enormous,” he said.

Amundsen went on to have more polar adventures. He flew the airship Norge from Norway to Alaska via the North Pole. This was the first transarctic flight across the North Pole. Amundsen had decided to conduct no more expeditions, but died in 1928 when his plane crashed during a rescue mission in search of a lost airship.

Great read on a slow, Corona lockdown morning. Thanks, David!

It does seem the British are great at coming second! (Maybe one or two exceptions)

Oddly, I’ve been reading about this in lockdown, too! Here in USA, I don’t remember learning much about either explorer. I feel more drawn toward Scott, who refused to let go of his scientific goals, even though he made so very many foolish decisions, like leaving home the mechanic who built his motorized sleds, and just…ponies. Still. From what I’ve read Amundsen swept in last minute with one goal: to beat Scott, who hadn’t undertaken this just for glory. In a snow cave near where Amundsen’s team set their flag after reaching the pole first, he apparently left a letter for the King of Norway with a note asking Scott to deliver it for him. That’s just poor sportsmanship. Still, the letter was found with Scott’s belongings when his body was found. My vote is for the poor, misguided Scott.

Fascinating. In that case, I would vote for Scott also.

You have misunderstood about the letter Amundsen left for Scott. It wasn’t poor sportsmanship at all. The return to Framheim was very dangerous (as the death of Scott and his men underlines) and in case they died on their way home, he left a letter for the King of Norway.